Volume 1, Issue 10

Anne Helen Peterson’s 2020 book Can’t Even offers a blunt read on the emotional dimensions of work today. Asking “How Work Got So Shitty,” she notes that more and more Gen Z and millennial practitioners work lonely hours as temps, adjuncts, freelancers, and subcontractors. “With assistance from our parents, society, and educators,” Peterson writes in Can’t Even, “we came to understand ourselves, consciously or not, as ‘human capital’: subjects to be optimized for better performance in the economy.”

Peterson’s writing makes me think of Augustine’s Confessions, especially where he tells the story of one of his own early-career gigs—giving a speech glowing up the emperor. Augustine felt so gross about the lies this job would require that he stalked through the streets of Milan trying to distract himself. Coming on a drunken beggar, he tossed the guy some coins. That’s all it took, Augustine noted, to make the fellow happy, just a few bright shiny objects. And yet, what was he himself about to do but give a speech to get the emperor to toss a few coins his way.

Sure, the beggar was a fool, living from booze to booze. But he “was undeniably happy while I was full of foreboding; he was carefree, I apprehensive.”

That lightning-flash revelation is vintage Augustine. It’s also a devastating parable for our time, when it is all too easy to find yourself doing a gig for higher-ups and hoping for coins.

Peterson, too, tells bitter truths about the emotional cost of early professional life. She asks why so many millennials today feel a sense of foreboding, why they feel so constantly apprehensive. Her own answer to these questions might best be described with Augustine’s devastating phrase cruel optimism. You may think you can grind your way to wealth, but only at the cost of yourself. Peterson writes,

If you subtract your ability to work, who are you? Is there a self left to excavate? Do you know what you like and don’t like when there’s no one there to watch, and no exhaustion to force you to choose the path of least resistance? Do you know how to move without always moving forward?

What does it profit anyone to gain another gig and lose their soul?

Peterson’s reflections tend towards the tragic. In contrast, The Mode/Switch, as you may have noticed, tends towards the annoyingly cheerful. Call it naivete on my part, and you’d probably be at least partly right. But whatever else it is, I hope this newsletter’s optimism isn’t cruel. My hope is grounded in the testimony of early-career professionals who see Peterson’s can’t even but raise her another sort of tale.

Take, for example, Christian Perry, a rising Black leader on Chicago’s south and west sides, who, despite being only 31, serves as the Deputy Political Director for J. B. Pritzker’s Illinois gubernatorial campaign. Christian shares his vocational story with the conversational ease of a community organizer. But he doesn’t hesitate to name the emotional exhaustion of early-career professional life as well.

Good lord, does this guy know how to hustle! He’s graduated from Trinity Christian College with a degree in political science, coached college ball, worked security, served in the Navy, started a nonprofit called Grind Grately—and then, as if all that wasn’t enough, Christian says, “God goes crazy.”

In 2018, Christian caught the eye of movers and shakers in Illinois and secured a job in the political sector, doubling his salary. In 2020, he and his wife Chakena organized a response to the murder of George Floyd, a Right to Breathe Rally for their nonprofit Black Millennial Renaissance. It proved to be the largest protest gathering in Chicago’s southern Cook County. Christian had begun drawing attention as far away as the state’s capitol in Springfield.

But at the same time, he was getting cues that things were not well with his soul. When the Navy called him up to service in the Horn of Africa, a doctor judged him unfit for duty, due to mental unwellness. Around that same time, he was nearly dismissed from his master’s program in public administration. Mental unhealth is not easy to talk about, but Christian is painfully honest about his own diagnosis.

As I look through my notes, I ask myself how Christian could sit across from me in our interview with such an easy smile just a few years after such hard times. Being a political operator in Chicago, after all, has involved him in the fragmentations of the gig economy, at least to the degree that Christian’s work obliges a lot of event-planning and event-going. I’ve come to think that what has saved him is attention to the affective and, more specifically, to the spiritual dimensions of vocation.

When burnout felt close, Christian made spiritual attentiveness central to his vocation. As he himself would say, he has learned to take his faith seriously in a political field that doesn’t always talk about faith.

Some of that spirituality has to do with what’s going on in his own life. He’s a person of prayer, he explains. But a good deal of his spirituality has to do with what’s happening around him, especially when it comes to the effects of racism in Chicagoland society generally and in faith-based communities in particular. (Racism in millennial professional experience, by the way, is something that Peterson has sometimes struggled to address adequately.)

I doubt Christian would be surprised by some of the white-guy obliviousness I myself have confessed in this podcast and this book. But I’m grateful for the ways that his interview made clear Christian’s calling to extend grace. God doesn’t make perfect people, he says. God makes good people. When he sees white people neglecting the urgency of racial reform, he extends what seems to me an amazing kindness and generosity.

Christian sometimes has to help his coworkers show grace, too. He tells a story about wrangling a spot for his candidate to appear at a lower-level politician’s gathering. If you’re a district-level operator, it’s a big and somewhat problematic deal to have a J. B. Pritzker swing by. On his way over to make sure things went well, Christian picked up smartphone chatter that his colleagues were giving the lower-level politician a headache by getting bossy. Christian, mindful of the grace the politician had showed them in the first place, called his coworkers and told them to back off, to let things breathe.

His number-one rule, he told me, is to leave an event with more friends than he came with. There it is again, that indispensable emotional and spiritual attentiveness, even when life and work feel tensioned and, well, sucky.

I still think Peterson is essentially right: work today is rarely kind to early-career professionals. The brutal pace and fragmentation of the gig economy make it all too easy for people, in Augustine’s phrase, to “pass over the mystery of themselves without a thought.” But here’s what I think I’ve learned from Christian Perry: emotional and spiritual attentiveness can add yes-ands to your can’t-evens.

Who I’m Learning From

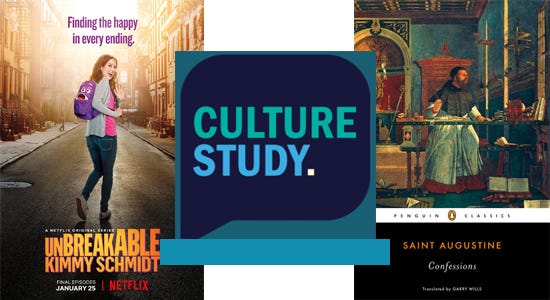

Thinking about hope in your vocation has me learning from voices old and new, from St. Augustine to Anne Helen Peterson.

Anne Helen Peterson’s Culture Study

Looking for a highly accessible translation of Augustine’s Confessions?

Share this post