The Flaw in Obsessing on Your Flaws

Your professional traits aren't good or bad. They're just yours.

I’m an introvert who can rarely think of what to say in the moment.

I’m a slow reader, easily distracted.

I’m a pleaser, but I’m also judgmental.

And I definitely let other people’s criticisms get into my head.

Those are qualities that shape my professional life everyday. And on most days, they are what I am inclined to call flaws. You could probably come up with a similar list about yourself, typing with one hand tied behind your back. But obsessing on your flaws is a little bit like trying to type with both hands tied behind your back.

(Pro tip: Never type with your nose. Use dictation software to avoid epistaxis.)

Here’s a mode switch worth making: re-describe your qualities as capabilities.1 Instead of obsessing on your not-so-awesome traits, learn to seem them as capabilities to exercise for the good of your workplace. (Think of a quality as a trait that’s relatively slow to change; think of a capability as a capacity that you can do relatively quickly and intuitively.)

So, how do you rethink your qualities as capabilities?

Two quick examples. Like I said, I’m an introvert who can never think of things to say. A definite flaw in committee meetings, right? You can think of a lot of jobs I’d be terrible at. Attorney. Salesperson. Trial lawyer. But what if I re-describe my introversion as a capability to work without external motivation? What if I re-describe my slow response time as a willingness to hear other people out? Suddenly, those flaws look like the powers I need to do my work as a researcher and professor.

I have a good friend who texted recently to say that she’s always been self-critical for how easily she gets bored. Then one day it occurred to her that her flexible attention equips her for agency work. What would make her a terrible lab technician makes her an amazing marketer. Every day she faces a dozen or more projects that she needs to push forward a little at a time. Her adjustable attention span is a valuable capability.

Maybe, she added, you should stop thinking about good and bad qualities and think of them simply as your qualities.

If you are a Morally Serious Person, you’re feeling uncomfortable right about now. I confess I’m feeling uncomfortable right about now—and I’m only morally serious, like, every other Tuesday or so. All this stuff about re-describing qualities as capabilities sounds like a recipe for rationalization.

But cast your mind back to one of the final scenes of Ted Lasso, season 3, when Roy Kent asks if people can change. Trent Crimp responds, “I don’t think people change per se as much as we just learn to accept how we’ve always been.” That’s a fair restatement of the moral point of this newsletter. Now, is it the only moral point you need in your work and life? No. Which is why, just a minute later, Coach Nate responds, “I think people can change. They can. Sometimes for the worse, sometimes for the better.” There are days when you need that moral observation, too.

But, look, there’s more than one enemy of the good, when it comes to professional life. Sure, you can be lazy about your shortcomings. But you can also be perfectionistic, and that’s an arguably more pernicious problem in a time when we’re constantly asked to compare ourselves with others on every screen and in every post.

Back to that scene in Ted Lasso. Coach Beard chimes in, “Change isn’t about trying to be perfect. Perfection sucks. Perfect is boring.” If you’ll forgive the contradiction, I think that’s perfectly put. Everything I’m trying to say here can be summed up this way: you’re not a perfect person, because you’re not a boring person. So, cut the self-recrimination and show some love for all your curious capabilities.

Let’s take a minute to think about why this mode switch from fixed qualities to flexible capabilities is hard to make at work.

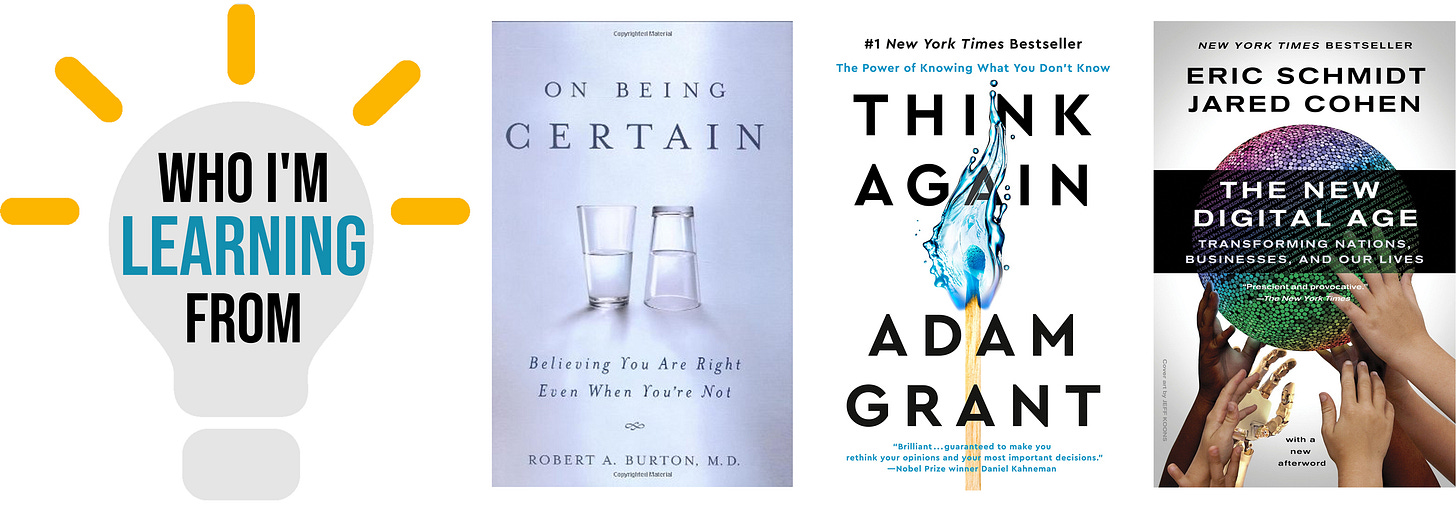

Most of our workplaces are highly changeable, highly accelerated environments that require a lot of mental shortcuts. Adam Grant’s recent book Think Again argues, “The accelerating pace of change means that we need to question our beliefs more readily than ever before” (17). In these quick-moving times, when everything’s tripling every few hours, it’s easy to fall back on efficiency moves just to survive.

Even when that means shortcutting ourselves.

You know one set of beliefs we’re slow to rethink? Our beliefs about our own flaws. Why is that? Maybe because, as Robert Burton says in On Being Certain, we too often “just know” things. We just know that we have all these flaws, so we slink around trying to mask them. We try to pass as perfect. How about, instead of just knowing your professional flaws, re-describing them as capabilities?

I think this mode switch has implications not just for you, but for your organizational culture as well. One upshot is that we can all afford to show more compassion for coworkers’ qualities.

If I have a colleague who always sees the downside in every proposal, can I learn to see this “pessimism” as a capability to be watchful and discerning?

If I have a coworker who is “blunt” and “impersonal,” can I learn to see her as attentive to process and committed to equity?

There’s one more thing to say about spotting capabilities in organizational culture: maybe you’re in the wrong organizational culture altogether. Perhaps, you’ve been berating yourself for professional failings that, when looked at afresh, indicate you’re better suited for another line of work entirely.

In that case, you need more than a mode switch. You need a career change. But that’s a subject for another newsletter.

-craig

When you’re beating yourself up about your qualities, try embracing a little Kelly Kapoor from The Office in your morning mantra.