Should You Care about Your Work?

What a recent Netflix thriller has to say about doing your job

“The overwhelm comes,” Rachel told me during a 2022 interview, “because you need to build up a brand.” But brand-building, she noted, often creates tensions with one’s own values. She described an exhausting urgency “to do my job without sacrificing what I personally believe in.”1

A year or so later, when I returned for a follow-up, I learned that Rachel had switched companies. She was still her adroit professional self and still asking the hard questions you ask yourself as well:

Should you invest your very self in the work you do? Should care about the job at all?

I had to think about such questions when, last weekend, Netflix released David Fincher’s, The Killer. As a revenge thriller, it’s only pretty good. It has neither the existential heft of Tony Scott’s Man on Fire nor the beauty of Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s The Revenant. But as a portrayal of the brutality and boredom of work in today’s digital economy, it’s a vital depiction of the professional art of not giving a—well, you know.

Artwork by Max Zhang, communication coordinator for the Mode/Switch

Michael Fassbender plays the assassin at the center of the film. After a job goes badly, his corporate clients invade his island home and torture his girlfriend. In response, the killer tracks down every person involved and does what he does best. (To be candid, I was glad for the 15-second skip-forward button: the story gets gruesome.)

Throughout the film, Fassbender’s voiceover free-associates about being a freelance killer in a corporatized economy. He hides out in a WeWork suite. He uses Amazon to get a fob duplicator. He rides a Tisto scooter and uses a different smartphone in every other scene. This man knows how to finesse the corporate digital economy.

The film makes the assassin’s job sound like a lazy girl job. His salary is large enough to allow him complete personal freedom. His to-do list puts a sharp line between professional obligations and private enjoyments. And he does lots and lots of yoga. He seems, in fact, to have too much time on his hands.

“If you are unable to endure boredom,” Fassbender’s character intones, “this work is not for you.” He sounds like a Gen Z wedding photographer, as he endures boredom and awaits just the right shot. We spend much of the movie watching him watch other people through a scope. (Hitchcock’s Rear Window is a very present influence.) But the the tedium also traces to the fact that doing this job well means not caring about much of anything. “If I’m effective, it’s because of one simple fact. I… don’t… give… a… f*ck.”

The assassin manages professional boredom by adhering to a strict set of rules:

Stick to your plan. Anticipate, don’t improvise. Trust no one. Never yield an advantage. Fight only the battle you’re paid to fight. Forbid empathy. Empathy is weakness. Weakness is vulnerability. Each and every step of the way, ask yourself, “What’s in it for me?”

As a code for life and work, these are small-minded certitudes, as shallow as they are pretentious. But even so, the script recalls some of what I’ve heard from rising professionals during interviews about a corporatized and digitalized economy.

Artwork by Max Zhang

As engrossing as I found The Killer—Fassbender’s coldly voyeuristic eyes are utterly absorbing—I was disappointed that the film didn’t actually question its own small-minded convictions.

Let’s make a mode/switch here: If someone were creating a psycho-thriller about your career, how might they script your rules for life and work? Here are some suggestions:

Never stick to the plan. Unlike the killer in this movie, you should not even pretend to anticipate all eventualities. Get used to not being able to plan your career in advance. Rachel told me once that her career has felt like falling downstairs, regaining her footing again, only to fall down another flight.

Find people to trust. The biggest flaw in The Killer’s depiction of work is individualism. But the same ideology emerges across the gig economy today, not least in the lazy girl job phenomenon. What’s broken in today’s professional spaces can’t be fixed by lonely action. As worker unions have been demonstrating, you need people.

Permit vulnerability. The movie assumes that brutality is essential to life and work today, which is why it preaches self-interestedness. And for many rising professionals today, that philosophy makes sense: corporations don’t care about you, and the digital economy reduces you to sellable data. But let’s make a distinction between loving yourself and securing yourself. It’s indispensable that you love yourself (you can’t care for anyone else otherwise), but it’s a vain pursuit to build a fortress around your life in the shape of yourself.

At every step of the way, ask yourself, “What gift might this moment hold?” You’ll hear my faith formation in what follows, perhaps, but I believe your work will go better if you assume that the universe is animated by love for detail and care for people. Not every season in your career will feel like grace, of course. But I think there’s wisdom in the question, Where is the gift in the here and now?2 Asking that question, even in the tedium and seeming pointlessness of corporate and digital spaces, is a better guide for life and work than the quest for power and advantage.

I suspect that script won’t get me a call from the Screenwriter’s Guild any time soon. Not even Michael Fassbender could make those words sound like Netflix drama. (Voiceovers are overrated anyway.) But your life, so far from being chic thriller with a cheap payoff, entails a resilient attention for the gifts that corporate work in a digital world so often obscures.

-craig

Have you watched The Killer? I’d love to get your take. Do you think the filmmaker believe in the assassin’s code? Fassbender’s character clearly does. But the film complicates his principles constantly. He is frequently forced to improvise. He suffers vulnerability and weakness. He fights battle after battle that he is not being paid to fight. He is driven by sorrow over the suffering of a loved one. Do you feel these contradictions in your work? Write to themodeswitch@gmail.com.

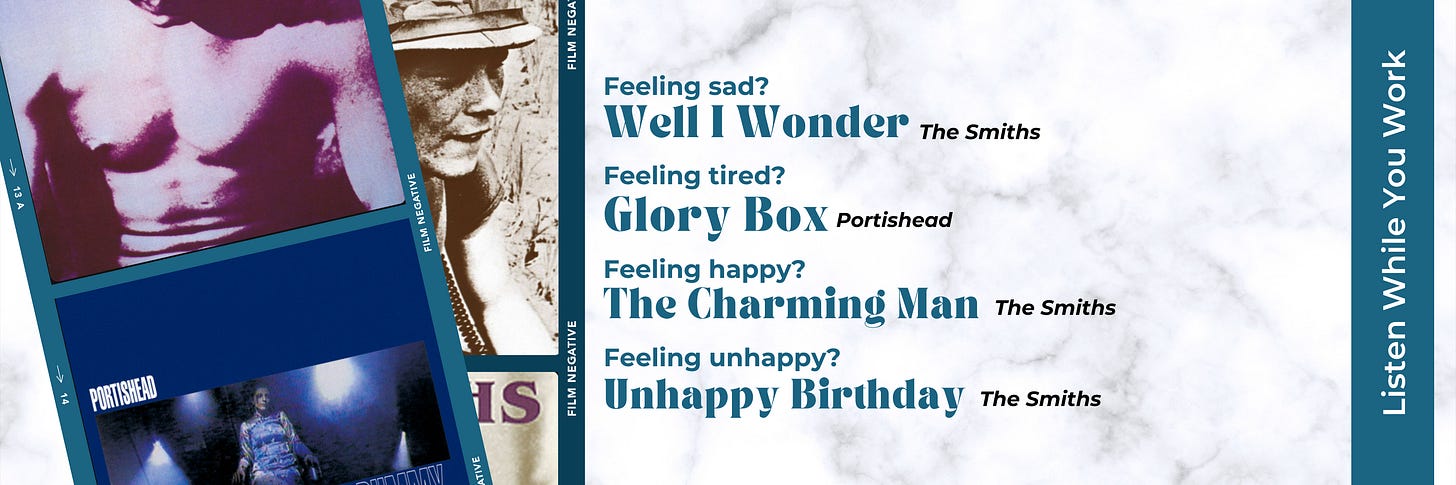

In The Killer, the main character uses playlists in order to concentrate. “I find music a useful distraction,” Fassbender’s character says. Okay, that sounds prosaic. But I loved his retro wired headphones and the clicking of his iPod as he scrolls. Max has put together tunes from the movie to listen while you work.

This interview transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

I wish I could cite specifically the author and book where I learned this question. I attribute it primarily to Richard Rohr.

"Each and every step of the way, ask yourself, “What’s in it for me?” As a code for life..." As you have pointed out, this quote can be extrapolated and related to our personal lives also. This line from the movie stuck with me the most. In my mind, it does not necessarily have to have a negative or selfish connotation or meaning. I took it as potentially having a positive, constructive, and pragmatic point and instruction to offer on how to navigate relationship situations in our personal lives. In other words, if a relationship with an individual or group of individuals is simply not serving us, or providing any significant benefit anymore, then we could or maybe should reflect on this and consider removing ourselves from that negative or toxic environment completely. This is something that I have found myself subsequently reflecting on in regards to my own personal life, and I believe that everyone would benefit from reflecting on. I can also see how this "philosophy/way of life" is acted out, excuse the pun, by Michael Fassbender's character in the movie, through his personal life choices, such as living with his wife in the seclusion of their home, surrounded by beautiful nature. Great article. Thanks.