You feel bad about your job. But how bad is bad? Bad enough to exit?

Velvet Rives knows bad feelings inside-out from working at J. P. Morgan/Chase. It’s not easy being a rising professional in a high-pressured corporate environment, but she was a fast learner, an empathetic colleague, thrived on tough deadlines, and was soon promoted. Still, she felt uneasy. One story explains why.

She had made friends with a veteran Chase employee, a senior coworker named Cynthia. Despite the generational gap between them, the two became close colleagues. And then one day, Cynthia made an error—a mistake that got her fired on the cusp of retirement. Velvet had written people up before. She’d seen people pink-slipped. And she’d always hated it. But after Cynthia, Velvet said, no more, and left Chase for work in the nonprofit sector.

Velvet Rives has now been happily employed for 6 years at the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology.

Back to the question we started with. How do you know when bad feelings mean you better go? It’s a hard question for two reasons.

Feelings depend on your brain’s guesses about how your body’s doing. That way of putting things comes out of emotions research by the neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett. In the book How Emotions Are Made, Dr. Barrett tells the story of a date with a guy she didn’t think she liked. Halfway through dinner, she started blushing, and her stomach gave a little flutter. She thought—"Wait, I must really like this guy!” Next morning, she found out she had a stomach bug.

She wasn’t in love; she was infected. Her brain had been guessing wrongly.

It didn’t take long in our interview for Velvet’s emotional intelligence to make itself known. When she took a job in the Family Institute at Northwestern University, she noticed that she started taking all her paid leave and coming back fatigued. She also noticed just how emotionally available her colleagues asked her to be. So, once again, Velvet left a job she was good at, a job where people admired her, a job where she’d been promoted.

So, is the mode switch in recommending for this week “Just go”? I don’t think so. Nor do I think that’s what Velvet would tell you. She’s careful about vocational decision-making and, like Dr. Barrett, seems alert to the emotion gaps that can open in the rush of life. Barrett would say that your brain is a pretty good guesser but can still be wrong. Velvet might want to talk, as she did to me, about the practice of fasting when it comes to job discernment.

So, is there a way to improve your brain’s emotional guesswork? You bet. But it might take a thesaurus.

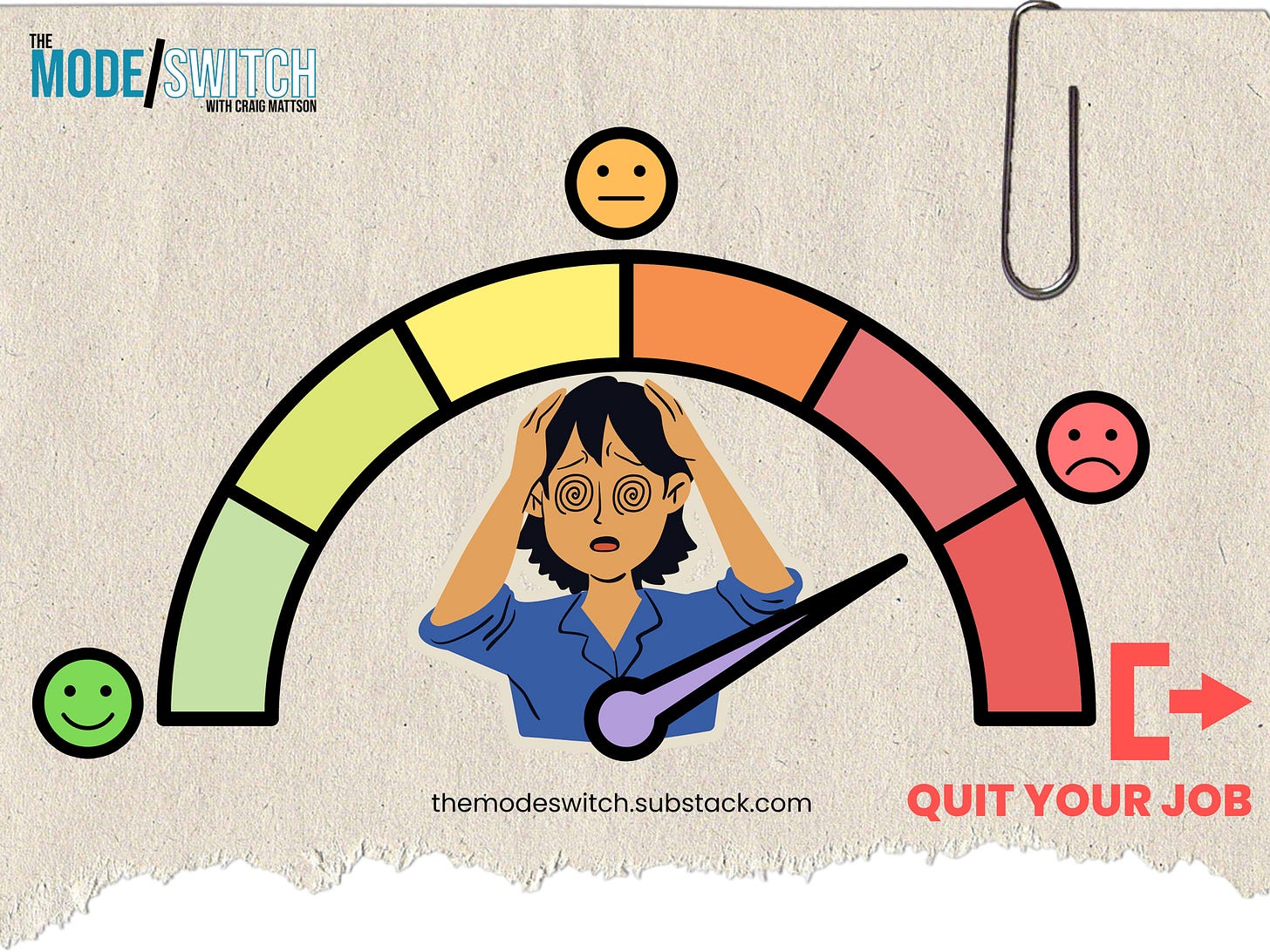

Feelings depend on your ability with language. Let’s do some right-clicking on how bad you’re feeling at work today. Bad’s a pretty open term. What kind of bad are we talking?

Each of those terms suggests a different path of response. Or come to think of it, you might feeling a better kind of “bad.” You might be feeling, This job is really pushing me right now, and it’s really uncomfortable—but you know, it’s kinda good to be growing again.

Barrett calls this “recategorizing how you feel.” (Her neuropsychology comes mighty close to communication theory, which ya gotta know makes me pretty happy.) The takeaway from recategorizing how you feel is that as you expand the range of your vocabulary, you expand the range of your feelings. And as you expand the range of your feelings, you expand the range of your agency.

One more thought. David Whyte suggests that what we call a bad feeling is a shredded piece of a fuller emotion. So, for instance, “being mad” is a remnant of a fuller emotion that involves deep compassion, profound care, and indignation. (Read his little essay on anger in Consolations to see what I mean.) I think what Barrett calls recategorizing Whyte might call reassembling the fullness of feelings at work.

You heard me talking above about Feldman (a neuropsychologist who can write) and Whyte (a poetic philosopher). But let’s give the last word to the main character Julie, in the Norwegian movie The Worst Person in the World: “Everything we feel, we have to put into words. Sometimes, I just want to feel things.” I feel that. You, too?