How come it used to be fun to check email? (Okay, well, in the very early 2000s, email was sorta fun for a minute.) And how has it become the most obnoxious and overwhelming aspect of work today? A couple of explanations:

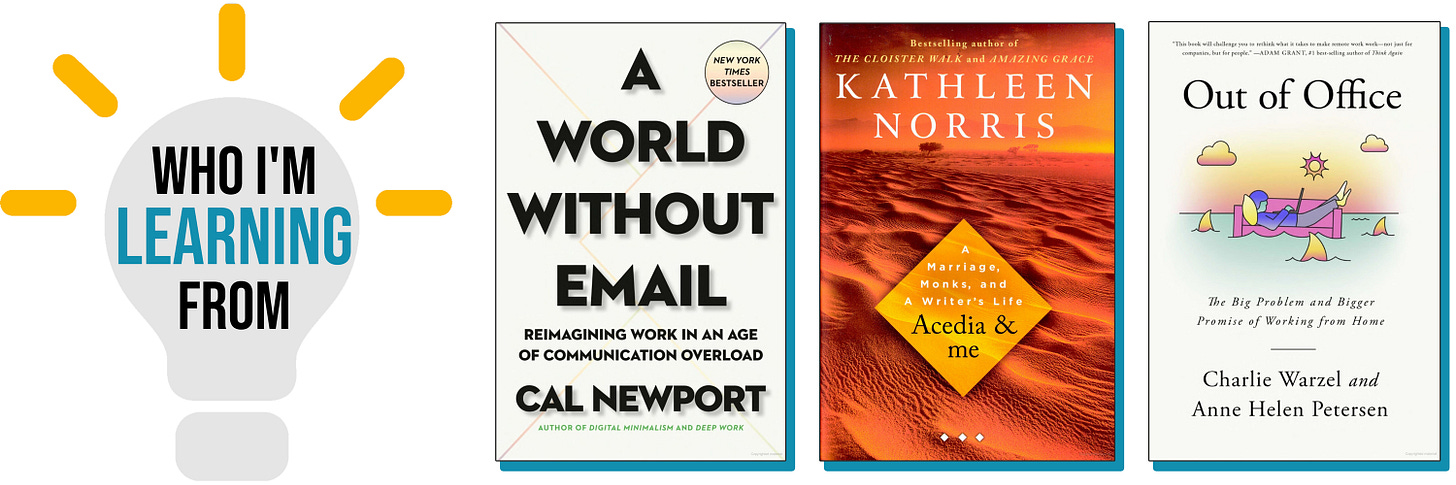

You feel you have to check email obsessively, or you’ll lose your job. Anne Helen Peterson and Charlie Wurzel note in their book Out of Office that today’s knowledge economy is a precarious economy. Rising professionals feel that they have to get good at email to impress their bosses. Peterson and Wurzel aren’t just talking about email; they’re talking about all the ways we turn ourselves into efficiency machines by reading get-organized blogs and downloading Notion and hacking everything process in sight. But one takeaway is that, because institutions are less and less committed to their employees, early career professionals have to demonstrate how useful they are by responding to every email within 3.4 seconds.

You are imprisoned in a work culture of constant email accountability. Cal Newport’s A World without Email argues that the knowledge economy has created “the hyperactive hivemind,” in which we are constantly sending and receiving messages. Instead of digging deeply into work we’re proud of, we have become expert senders of digital things. It’s irresistible. Email combines the quickness of one-on-one conversation with the ease of asynchronous communication. But somehow this admirable arrangement has made you feel like there’s a crowd of 250 people everywhere you go, each waving madly and saying they hope this message finds you well.

I respect these critiques. They name the power abuse that happens when it’s just too easy for managers to send early careerists late-night tasks. They also name the ways that email does more than shuttle information around. It also shapes workplace culture.

But I think those explanations are necessary but insufficient. The third reason I’d add is that professionals are afraid of being bored.

Seriously, being a person rarely manages to be interesting. I don’t know why this is, exactly. Original sin? A glitch in the matrix? An approaching expiration date on our species?

But for whatever reason, there are huge swaths of our lives where we’re just, you know, waiting for things to happen. So, we check our email.

One of the dubious promises of digital communication is the elimination of boredom. Checking email does that. But there’s a surcharge to the soul.

Third-century contemplatives talked a lot about the deadly sin of acedia, also known as sloth. But what’s so bad about sloth? It’s just laziness, right? And whatever else you can say about the intern working remotely from her Macbook at the kitchen table, you can’t accuse her of laziness. But hold on. Ancient thinkers didn’t think sloth was laziness merely; they saw it as an inability to care. Acedia, in other words, feels like nothing matters. It feels like dullness and melancholy. Kathleen Norris has suggested that “much of the restless boredom, frantic escapism, commitment phobia, and enervating despair that plagues us today is the ancient demon of acedia in modern dress.”

Today, we could track workplace acedia in a cycle of misbegotten digital busyness:

This is the condition that all too many critiques of email culture miss. It’s not just that I check my email because I’ll get fired if I don’t. Nor is it that I check my email because there’s a bias towards hyperactivity in the workplace today. No, I check my email because I can’t bear to stay with something. I can’t bear the loneliness of concentrating on one thing for longer than a few minutes. I can’t bear the pain of waiting for those unobvious gifts that come when we sit still and look and think.

What does all this mean for you as a rising professional? My hunch is that if you want a job in the knowledge economy, you just about have to show your willingness to the Cocaine Bear of busyness. But what would happen to our workplace communities if incoming professionals let it be known that their best quality isn’t relentless diligence so much as resilient attention?

What if your subtle flex in your next job interview was your capacity for concentrating on one thing for a really, really long time?

What if your what-is-your-greatest-strength answer was that you never check email after supper? (For your greatest weakness, you can still say you “care too much,” if you feel you must.)

What if the HR committee saw in your byline this inspired sentence from the pod immediately below: “I may be sending this message at a time when you’re not working. Life is full of other good things besides email, so please don’t feel obligated to respond immediately!”

I think Wurzel, Peterson, and Newport are shrewd analysts of what’s gone wrong in email culture today. You should read their books. But even if we improve our systems and eliminate our hyperactivity , we won’t have solved our email problem. Those authors help us see how our email crisis is partly about power, partly about process. But they overlook that it’s also about presence.

I don’t just mean physical presence. Digital presence, too, is an indispensable quality. But if we want to address the sickness of email in our workplace communities we’ll have to shift our values from efficiency to presence. I mean being willing to be present to life as it is there to be lived and to work as it is there to be done and to people as they are there to be loved.

-craig