I’m writing this week’s newsletter on a bus from New Orleans to Montgomery. This pilgrimage retraces enslavement history from the Whitney Plantation to the back stoop of Medger Evers’s suburban home all the way to the Pettus Bridge in Selma.

It ain’t sunshine and grits, ya’all. There’s anger driving this week’s newsletter.

Still, I’m determined to publish this week, because I’ve learned two stories you need to hear, especially if you’ve had an uncomfortable sense that something’s not right in your organization.

The first is Dyvon’s tale as a manager in a soul-killing startup.

The second is Adrian’s narrative of a sex-trafficking ring her boss was running.

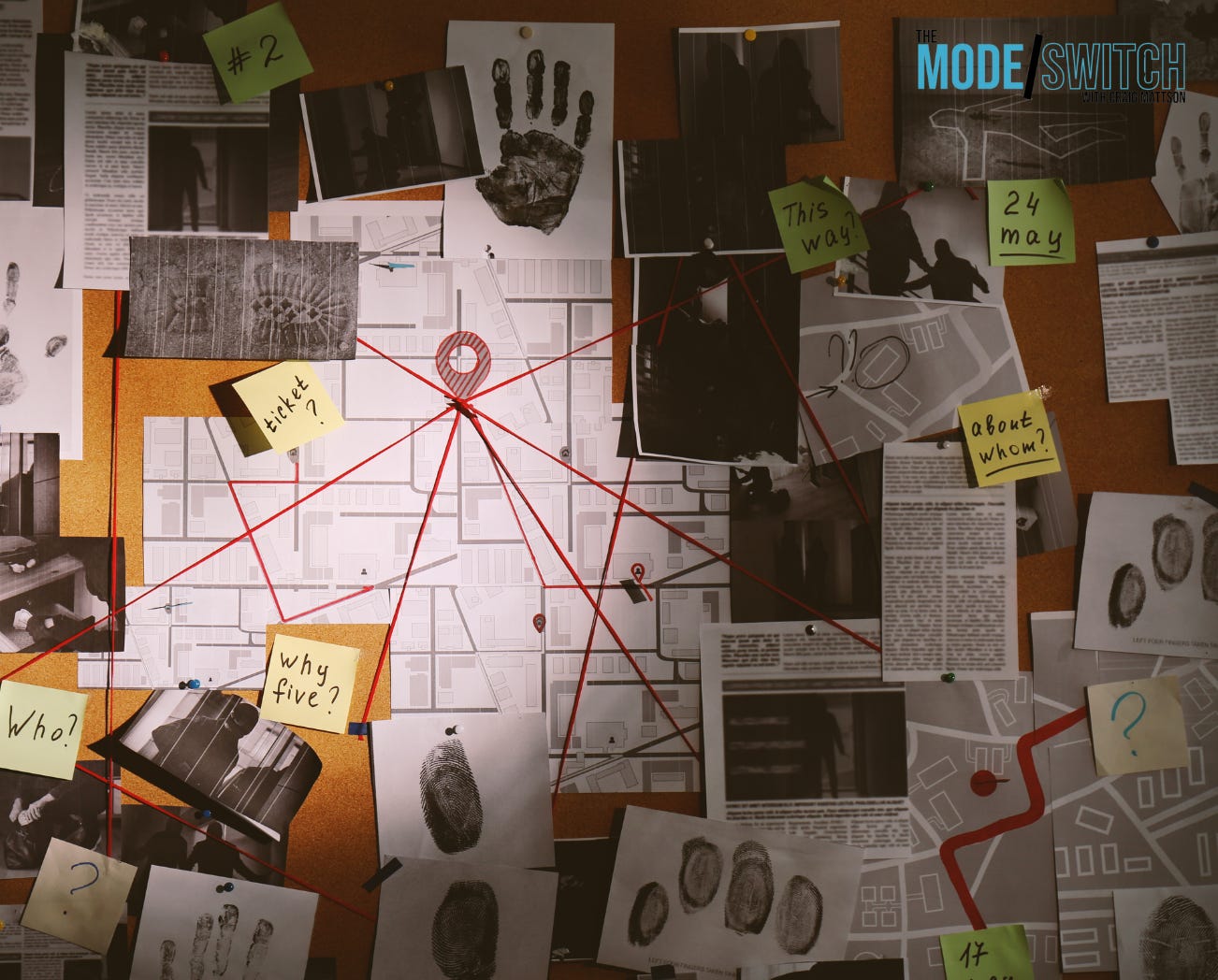

We gotta talk about the evidence, people, the evidence that’s all too easily lost on us, the evidence that something’s rotten in corporate and institutional life today.

We need you to keep your wits about you, and here are two stories why.

Following the leads in a company cult (story #1)

Picture Juneteenth, 2021. Dyvon and the five other Black employees of an L.A.-based startup get an invitation to plan a presentation to the company about liberation from American enslavement. Was this an opportunity to do some consciousness-raising and culture-transformation? Maybe. “But with two days’ notice, we were expected to do the work our public school system and government had suppressed for decades.” As Dyvon and his coworkers went back to their tasks, shaking their heads, they couldn’t help recalling other instances of racial obliviousness and sometimes aggression in their company.

The company’s everyday operations were predatory. They took over spaces that had employed minority entrepreneurs. They bought property, displacing residents. They beefed up police presence in communities of color.

The company boasted a diverse workforce. “But,” says Dyvon, “only low-level functions were typically diverse at all. Sometimes white women held leadership. That was pretty common. But other than that, it was incredibly rare that anyone other than a white man would make decisions.”

A big part of the problem, as Dyvon noted, was that the company ran like a cult. The C-suite comported themselves like Greek deities, arbitrary and aggressive. Sure, when they made decisions, they tried to cast them as rational and data-driven. But in actuality, the choices felt irrational and data-vacant. They handled controversy by drowning conversations in so many statistics that it was impossible to keep up. Dyvon recalls seeing slide after slide with sometimes as many as 80 datapoints justifying a decision. But the connection between the data and the decision? Nonexistent.

My company was a cult….Executive decisions were cloaked in closed-door conversations, and they spoke with conviction but no data in what appeared to be data-driven decisions. “We’re ending work from home as we’ve seen productivity drop.”“We’re planning to merge these entities because our data shows that closer integrations will unlock new revenue for both parties.” “We’re no longer operating in that region because the money just wasn’t there.” In each situation, millions of dollars and hundreds of workers would be affected…. - Dyvon

Dyvon was promised a raise within three months. Six months later, nothing had happened. He advocated for himself and finally got the raise nine months after promised. Because of other cuts, his raise actually entailed a decrease in pay.

He advocated for his team to get raises. The higher-ups agreed, but the promises fell through. “I had to stand before my team, hands tied, just as all of my bosses before me at this company had, making empty promises and giving false updates, unable to make change for people.”

Juneteenth rolled around, and everybody was given the day off—except for people with critical positions. 4 of the 6 Black employees held critical positions with the result that a holiday designed to celebrate African American freedom instead gave the day off for Whites and kept most of the Black employees in the office.

Dyvon later parted ways with his company after signing an NDA. But the departure brought him still more loss. “This experience devastated my mental health and, due to that, my finances.” I received his story in an emailed letter that concluded by saying that, for the first time in several years, Dyvon had felt a week of consistent happiness.

I hope he has many more good days. But his story raises the question of what you should do when you get clues that your company is bad for the world.

Connecting the dots in a company hiding dark secrets (story #2)

Adrian told me a story about one Halloween when one of her bosses came to work dressed as a pimp. “I’m running a business here, ladies,” he shouted, hoping for laughs. But as Adrian looked around at her fellow employees in their special occasions retail, all of whom were women under the age of 30, the joke didn’t feel funny.

The pimp costume felt like it was blurting an open secret. It was, but Adrian didn’t know it yet.

Nobody had job titles on this site—nobody, except for the twenty-six-year-old, super thin blonde who was Vice President for Marketing. Everybody was working for very low wages. Everybody was asked to do weekend work. Nobody had a job description.

Adrian found herself managing purchasing for the company, tracking inventory, purchasing gowns from China, hiring models for shoots and shows. When she asked for a raise, another of her bosses said, “To be honest, you’re kind of slow.” Adrian protested she was getting things done. And the guy said, “No, that’s all good. I just mean, when you get up from your desk, you move kinda lazy. You need more urgency, like the other girls.”

When you’re in your late 20s, early 30s, an accusation like that hits hard.

“Who can work this weekend?” one boss yelled out. No hands went up. Every eye looked down. “Well, that’s just fine,” he said breaking the silence, “but I am going to remember this, next time any of you asks for medical leave.”

One day, one of the models was limping, and Adrian tried to help her. The girl’s foot was bleeding. “Being a model is hard,” Adrian told me, and some of these models were in their teens. But as she was trying to help the girl out, a boss came tearing backstage. “I don’t give a f*ck if her feet are bleeding, she is going to walk that runway.”

The Department of Justice finally caught up with one of the bosses a few months after Adrian found another job. One day, she got a Facebook message, saying that the guy had been arrested for sex trafficking. He’d been a part of a 36-person ring of traffickers who lured Thai women to the U.S. and forced them into sex slavery.

Listening to Adrian’s recording for this story, I could hear her anger 15 years later. “I can’t believe that I ever let this absolute piece-of-shit human make me feel bad.”

Finding the courage to suss out the truth

You may feel tempted to treat Dyvon’s and Adrian’s narratives as true crime stories. Entertaining. Lurid. Hyped. But institutions, corporations, companies, nonprofits are all too often scenes for misdeeds.

The tough thing for you, for all of us, is that when you feel overworked or under-resourced, your organizational attention feels most scarce.

Let me close, then, with an encouragement to cultivate what Adrian called “asshole-dar”—but which I’ll call the brave intuition that is your native gift. You don’t have to keep your head down. You don’t have to just keep scrolling. But you do need to exercise brave intuition rather than docile compliance.

I told you earlier that I’m on a civil-rights pilgrimage. At one stop, my team witnessed the stories of two Black exonerees—Robert Jones and Jerome Morgan—wrongly convicted of crimes and then only very belatedly released from a Louisiana prison after the legal system was forced to conclude their innocence. Morgan lost just shy of 20 years of life, and Jones lost 23, to the penitentiary.

One thing Morgan said is sticking with me: do not be in awe of your institutions. These men studied and organized and fought to prove their innocence. At every step, the American legal system obstructed their way. In their shoes, I would have despaired. But these men simply refused to be intimidated.

I think it’s especially easy for rising professionals to be cowed by their companies. But, really, for anyone of any generation, intimidation comes naturally.

Maybe you’re a privileged person with a basically benevolent view of institutions.

Or maybe your parents brought you up to be respectful.

You might even hope that, if you’re kind, your company will be kind to you.

You may well fear your hunch that something’s not right must be wrong.

But don’t be in awe of your institution. Your company’s a social construction with its own rules and squares and pawns. If you’re tracing toxicity, if you’re sensing way too much restructuring going on, if you’re registering a refusal to acknowledge the merest truths, why then, the game’s afoot.

What I’m Up to These Days…

Reading: How the Word Is Passed by Clint Smith.

Traveling: Civil-rights pilgrimage from New Orleans to Jackson to Selma and Montgomery. I give thanks for gains made in equity and justice across American society, but the trip’s teaching the sad dynamics of racism, sexism, and other abuses shaping American work culture still today. A lot of work yet to do!

Watching: True Detective, Season 1, perfect for driving through Louisiana bayou country. Rusty’s also got a quotation that chimes in with this week’s issue: “I had my time where I wondered if this was all in my head. That time passed.”

Celebrating: So great to see so many new subscribers joining the Mode/Switch crew. Glad to have you along!

And now, for the inspiration for this week’s crime narratives:

The original idea for this week’s Mode/Switch came from a reader pointing out the connection between Reesa Tessa’s Who TF Did I Marry? series and the true crime of red-flag managers in poisonous corporations.

Feeling behind on this 52-part TikTok phenom? Check this recap out.

But watch out, this video series has triggered some serious watch-while-you-work addictions!

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser