Vol. 1, Issue 29

Frederick Buechner (beek-ner) died this week at the age of 96. He was a novelist, an essayist, a preacher, and—most pertinently for this vocation-focused newsletter—the person who told us to seek “the place where our deep gladness meets the world's deep need.” The phrase traces to Buechner’s book Wishful Thinking.

Frederick Buechner, from his Amazon page

Even so, I wish those words about deep gladness and deep need weren’t so easily quotable. At least from where I sit, after a year of asking early-career professionals how they’re dealing with vocational overwhelm, I think that it’s not just that the world has great need. It’s that the world appears to be ending.

Carlo Rotella’s book, The World Is Always Coming to an End addresses conditions in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood. But he might just as easily have been writing about Donbas or Taipei City or Beirut. Or your city. Or mine.

This morning, after reading of Buechner’s death, I went crawling through some basement boxes looking for the first volume I read by him back in the mid 90s: The Alphabet of Grace. My family’s just moved, so all our books are shut in alphabetically labeled boxes. But I could not, even in quest of deep gladness and with great need, find the box with the B books. The thirty-year-old paperback proved as elusive as Buechner’s God.

To Google books I went and soon was scrolling through The Alphabet of Grace. I could feel immediately the air patterns of his prose. Each sentence breathes something out and then withdraws it partially, qualifies it, and then expels it forward, always approaching its conclusion indirectly. It’s difficult to read Buechner quickly, because his prose is all about what he calls “the approach of the approach.” He’s writing his way close to something always about to arrive.

So, I take that back, what I said earlier about the elusiveness of Buechner’s God. Not elusive, exactly. Not absent. But just about to arrive.

At the beginning of Alphabet, Buechner relates a story from one of his own novels, an account of a young man lying on his back in the grass, pleading for God to manifest in a way he can recognize. “His heart pounded, and he did not dare open his eyes not from fear of what he might see but of what he might not see, so sure now, crazily, that if ever it was going to happen, whatever it was that happened…it must happen now in this unlikely place as always in unlikely places.” But when he glances about after a moment, he sees only, “the most superbly humdrum stand of neglected trees with somebody’s shoe in the high grass and a broken ladder leaning, the dappled rot of last year’s leaves.”

That line about superb humdrumness gets to me. How can something be excellently ordinary? But the line makes me think of a research interview from just this week, when I asked a rabbi and entrepreneur named Elan Babchuck about the role of spirituality in his vocation.

I think it's the inviting myself, pushing myself, holding myself accountable to the knowledge that there is a person on the other side of this communication who is made in the divine image and therefore has infinite value. And with that mindset, with that reminder, let's say, how, might I respond or react to this input in a way that elevates that person’s dignity? That for me is the greatest spiritual practice that I can maintain.

Rabbi Elan Babchuck

What I admire about Elan’s practice is how he queries superbly humdrum conditions. But I think that, at least at first, I missed the Buechner-like expectancy in Elan’s question. After reading and re-reading the transcript, I’m thinking about his words this way. When you’re at work, talking with someone in the mailroom, or maybe avoiding talking to someone in the mailroom, what are you hoping for? If you’re like me, you have low expectations. The small talk is humdrum. Nothing to see here, folks, let’s just keep moving.

But Elan’s question anticipates a hidden reality and a live possibility. The hidden reality is the glory of the person in front of him. The possibility is that communication might make that glory more visible.

So, back to Buechner’s young man lying in the grass. He’s also asking expectant questions, also hoping for the invisible to become visible. Oh, I should say that a few paragraphs later, Buechner confesses that this story is autobiographical. He is the young fellow in the grass. Uncanny how a book brings a youthful past into our present, even in this week when we’re missing the 96-year-old now gone into his mysterious future.

What the young man hears, lying on his back, is not the divine voice, but a tiny sound: “Two apple branches struck against each other with the limber clack of wood on wood. That was all—a tick-tock rattle of branches…”

I remember reading those words in my 20s and feeling a little underwhelmed. What was it about two branches striking each other that gave the author (as Buechner wrote) “a great lump in his throat and a crazy grin”? But now, at what keeps feeling like the end of the world, I think Buechner corrects for two ways that we miss the superb in the humdrumness of everyday vocation.

The first is thinking that our experience should be transparent to our understanding. These days feel like the end of the world, but (as this wonderful piece by Eleanor Parker notes) the world has come to similar ends before. History simply isn’t transparent to us. Nor is personal experience.

The second is thinking that our experience has nothing superb to witness. For Buechner as a young person stepping out on what would be a long and productive life, those two branches knocking revealed the world anew. He said it was like standing on one side of a doorway waiting for someone to walk through. Nobody had yet walked through. But there was suddenly a super-charged possibility that someone could walk through at any moment. Think of those times when you know that the person you’re talking to is trying ever so subtly, ever so desperately, not to laugh, and you feel mad at them, because you’re trying to tell a serious story, but now you’re laughing, too. That’s the faith Buechner’s book encourages, and it is, in part, an expectancy that the world keeps beginning again.

Rest in peace, Frederick Buechner, and pray for us all.

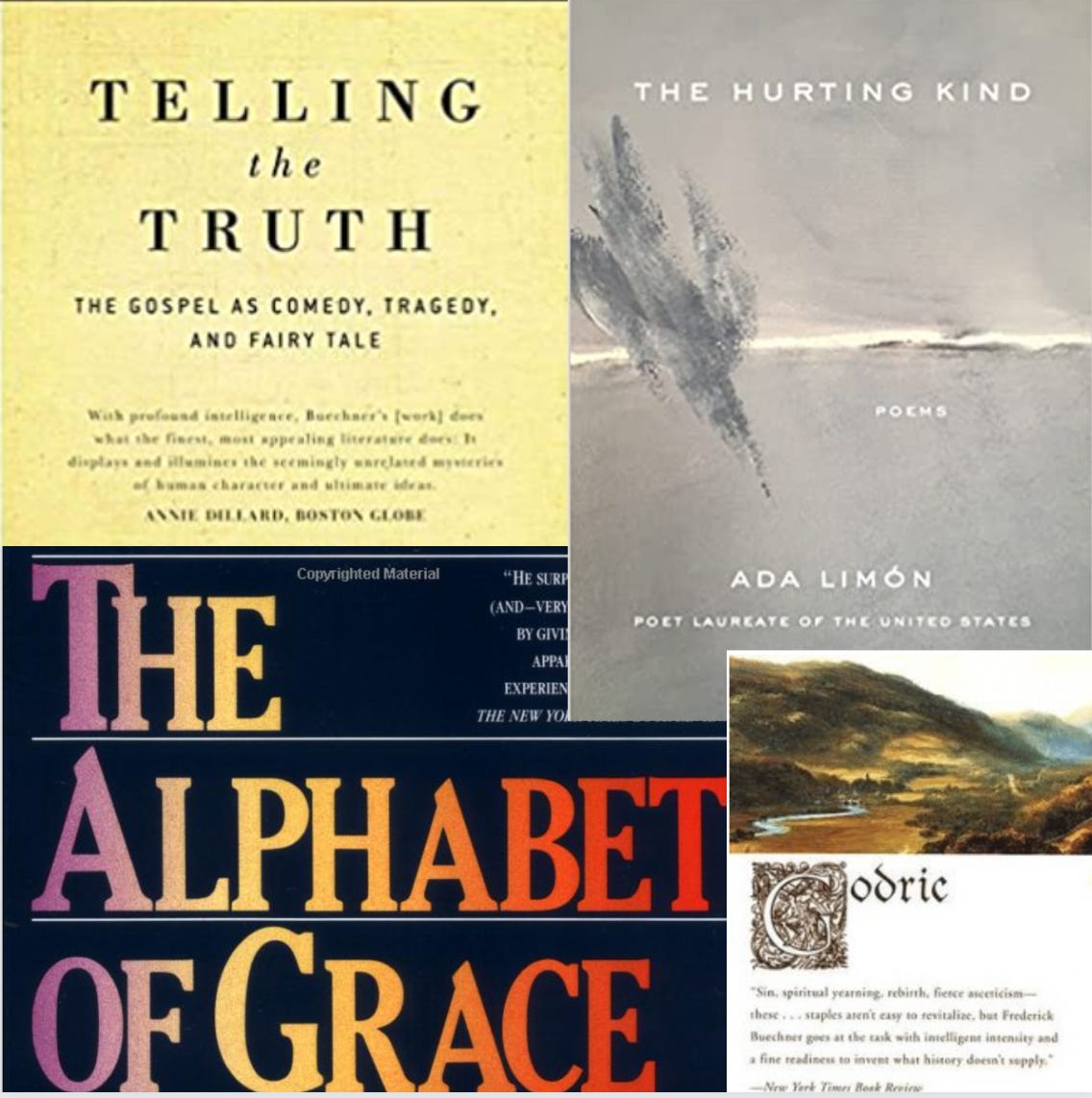

Who I’m Learning From

In commemoration of Buechner, I’ve put up images of the three books I know best, but, oh my, there are many other good ones. I hope you try him out. I’ve also included a visual reference to our new poet laureate, Ada Limon. Her poem “Lover” says something adjacent to Buechner’s insight about expectancy—and also includes the line that inspired the title for this Mode/Switch: “I trust the world to come back,” writes Limon. You can read the entire poem here, and you should.