People don’t get what you do. Not really, not sufficiently. They should, because you’re kind of amazing. [Editor: revise to eliminate appearance of pandering?] But nobody, not your roommate, not your partner, not your Labradoodle, nobody understands all the stuff you do. And I’m here to say why that’s okay.

But let’s start with why it sucks.

When Shelly Bauble sat for an interview with me, she narrated the paradoxical obscurity of her work. On the one hand, she had been a prominent television reporter in three markets, two of them in major metropolitan areas. On the other hand, she often found herself working in an exhausting solitude, capturing her own interviews on scene, filming her own standup reports from the street, shuttling fresh footage to the station for airing. The stress could be terrific, she said, especially seeing all the trauma. Reporters are early responders to accident and crime scenes; they hear the police officer trying to explain what happened to a family member. And they hear the shrieks of grief torn from the bereft. Shelly had to somehow pull it together enough to record a spot and then get home to recover. But she was never really off the job, never far from her phone doing its angry vibratory dance on the bedside table at 11:30 PM. Nobody saw her pull on her parka and head out into the dark streets. I should say, too, that Shelly has moved onto another line of work in medical corporate communications.

Translating the details of your work for someone unfamiliar with it strengthens your grasp of what you actually do.

You could tell your own versions of Shelly’s story, I’m sure. You know what it is to labor in relative unknownness. In fact, I would wager good money that there are at least three kinds of people who fail to understand your job:

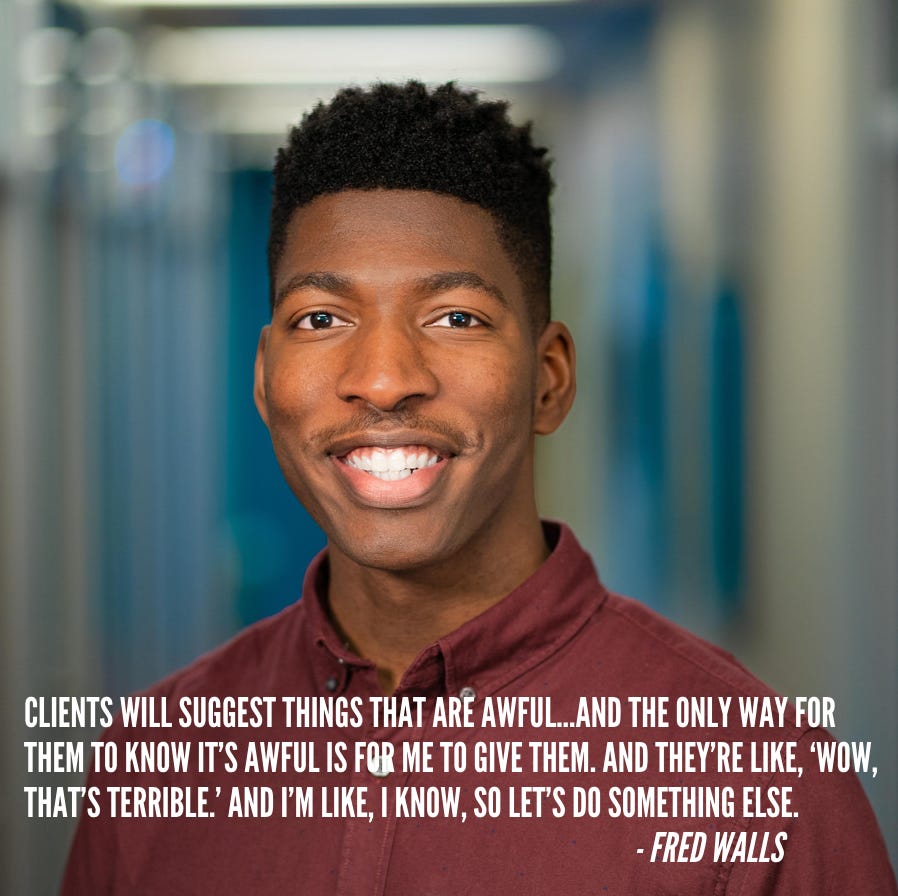

Let’s start with your clients. Even the people who hire you to do a thing assume, paradoxically, that they know as much as you about your expertise. When I asked Fred Walls if there’s ever a gap between what he knows will work and what his client thinks will work in a given shoot, he said, “Every single day. Every single project I work on.” He added, “A lot of times clients will suggest things that are awful, and I know they’re awful. But they don’t know that. And the only way for them to know it’s awful is for me to give them. And they’re like, ‘Wow, that’s terrible.’ And I’m like, ‘I know, so let’s do something else.’”

And then, there’s your friends. A ceramic artist—let’s call her Maggie—told me that when she tells people what she does in her shop, they will say, in effect, “Oh yeah, I almost did that. But then I got wise.” It makes Maggie feel somehow that she should say sorry for putting in 70 studio hours a week. In a similar vein, a communication professional told me a story about a truly strange brand expression her company had attempted on TikTok. After we had finished laughing, she shook her head and said, “I can’t tell that story to my friends; they don’t understand my work.”

And finally, there’s your higher-ups. Javairia Taylor told me the story about a new project manager at her company, a blunt guy with a military background, who developed a dislike for another employee and was always trying to fire her for the smallest errors. Javairia had to hold him back: "No, it does not work like that. We’re not going to fire someone without documentation.” Similarly, Kara Cunningham told me about a time when a well-muscled kid in her public school program got upset and started spinning around. Before Kara could make sense of what was going on, he jumped her, attacked her. Her coworker pulled the boy off, fortunately, but when Kara reported the incident to her higher-ups, they told her—I kid you not—to grow a pair.

Why not treat the quiet specialty of your job as a chance to practice coordination with people who really don’t get what you do?

Clearly, there’s some desolation in doing work that people don’t take the time to understand. So, how could it ever be good that people don’t understand what you do? I’d like to suggest, on the basis of my research among early-career professionals, and my study of communication theory, that this experience of vocational inconspicuousness teaches you some vital practices.

The practice of translation. I think it was C. S. Lewis who said that you really don’t understand something until you can explain it to a child. The same thing goes for supervisors and neighbors and spouses! Translating the details of your work for someone who knows nothing about it strengthens your grasp of your field.

The practice of coordination. John Durham Peters deconstructs what he calls “the dream of communication” in which you enjoy flawless connectivity with another person. But in highly specialized, highly fragmented workplaces, that connectedness is just not going to happen. Most of the time, you experience other people and their work as full-on strange. So, there’s real value in going along to get along—that is, saying yes to people whose work you don’t understand and who find your job just as mysterious. Sometimes, the goal is coordination, as Peters might say, not communion.

The practice of contemplation. This might be the hardest counsel in this week’s Mode/Switch. But when somebody overlooks or misunderstands your work, there’s real benefit for your own soul in simply keeping quiet. Not only is that kind of watchfulness a source of strength, freeing you from the addiction of impressing other people, but it also makes collaboration possible. The Orthodox writer John Chryssavgis has said that silence “is the pause that holds together—indeed, it makes sense of—all the words.” It sounds strange, but the quickest way to help someone understand your work may be to simply say nothing.

Derek Thompson runs a newsletter called Work in Progress, in which he recently asked people to tell him “what don’t people get about your job.” The question mattered to him, he explained, because “I live in an economy of labor specialization, which means that my life depends on a tapestry of labor that is ultimately inscrutable to me. I buy coffee that I don’t know how to harvest or package. I drive a car that I don’t know how to build or repair. I live in a home that I don’t know how to construct… I’d like to be a bit less alienated from the production of my own existence.”

We all need more Dereks in our lives, I guess. But if you don’t happen to have one on hand, you can still treat the quiet specialty of your work as a chance to practice translation, coordination, and contemplation.

And how about this: next time you’re at a party, don’t ask “So what do you do?” Ask instead, “What do you do that nobody understands?”

Hey, thanks for checking out the Mode/Switch for this week. I’d tell you more about what goes into crafting each issue of this newsletter, but I’m gonna take my advice above on that point. What I would appreciate is your sharing this with an early-career professional in your workplace.