It's Not Just Her Problem

Dealing with Sexual Harassment in Organizational Community

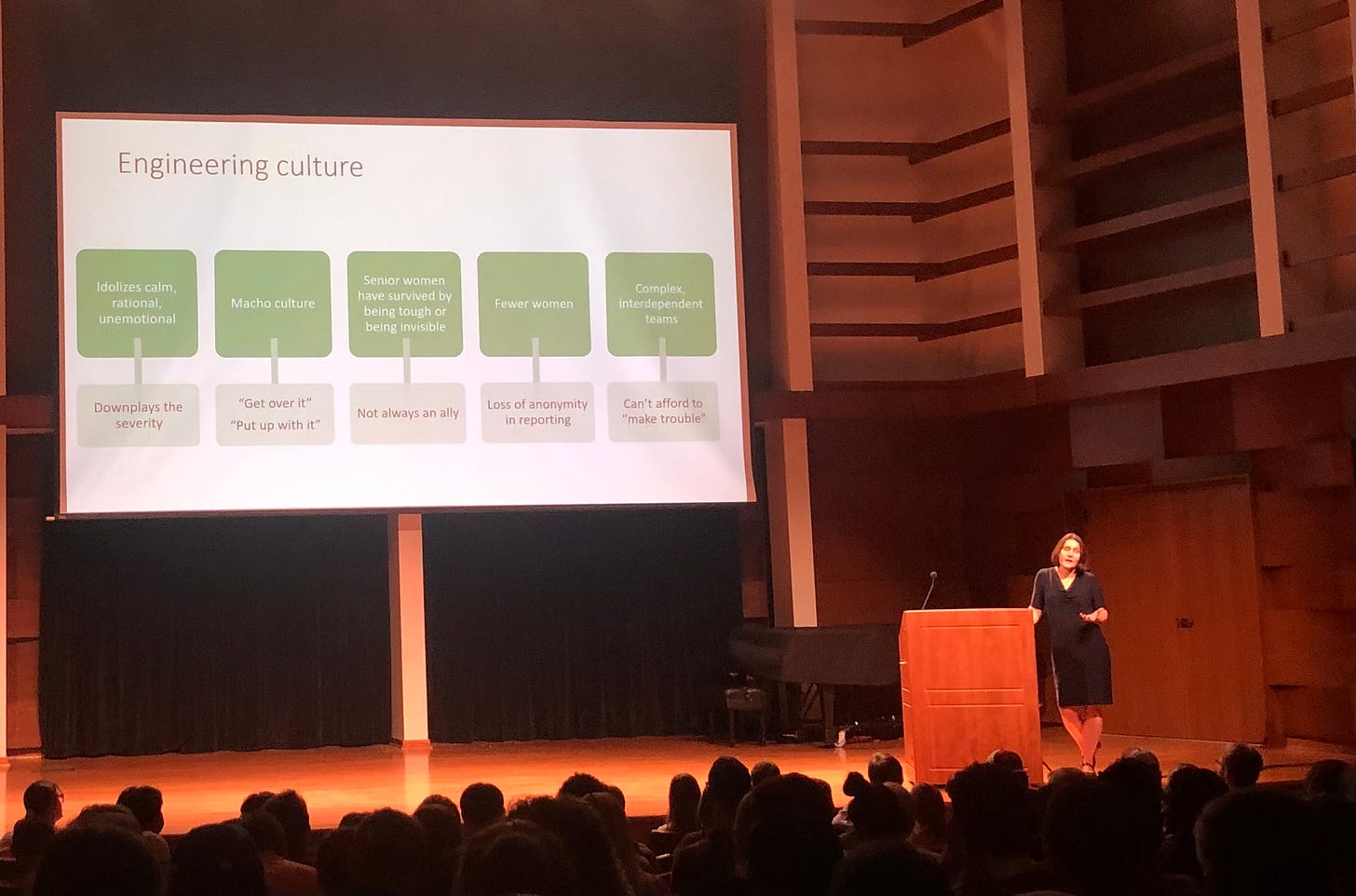

How come The Mode/Switch has never discussed sexual harassment for early-career professionals? Has this been due to my own dudely, Gen Xer blindspot? I started thinking so after attending a seminar by Professor Jennifer Van Antwerp, presenting findings from a book she’s co-authored with Denise Wilson: Sex, Gender and Engineering: Harassment at Work and in School (Cambridge Scholars). When I arrived at the recital hall for the talk at Calvin University, I expected a handful of faculty members standing around eating cake and chatting up the book. Instead, the auditorium was packed. And I got some much needed schooling.

After hearing Jennifer’s talk, I asked her if she’d sit down for a Mode/Switch interview. Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

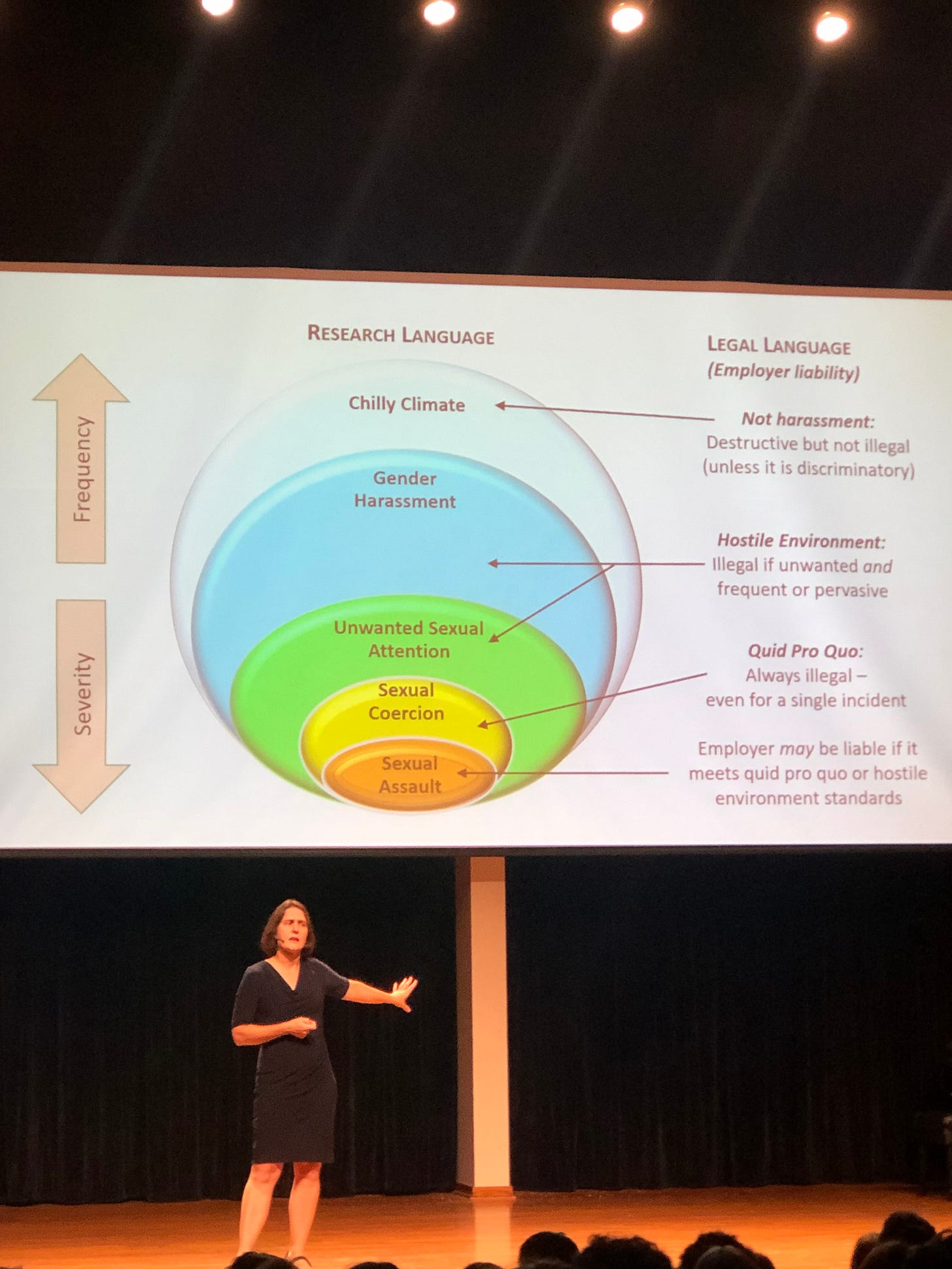

Craig: How do you define sexual harassment?

Jennifer: We define it the way the research does. There's sexual coercion. There's unwanted attention, an inappropriate expression of sexual or romantic interest. And then, gender harassment can be targeted at individual person, but the real target is the gender.

Once you expand to gender harassment, of course, there's LGBT types of and we would separate heterosexist harassment from transgender harassment or non-binary binary genders, but there's just not enough data yet about LGBTQ in engineering.

Craig: I wonder, doing this research, how has it compelled you to rethink your own vocational story?

Jennifer: I've never had a workplace situation where I just get pummeled with harassment again and again and again. I only have isolated incidents. I was at a conference of engineering educators, a round-table kind of discussion, and we needed a recorder. An older man turned right to me, the 30-year-old woman, and said, “Why don't you be our recorder?”

I knew that women in engineering settings get assigned these housekeeping tasks, so I decided to push back, and I said, “You know, I'd rather not—I think that's not a good fit for me.” He pushed back: “No, really. You look like you have good handwriting. Why don't you do it?”

Well, that was startling. What does someone with good handwriting look like?

There were young men my age there too, and they all looked at their shoes. I ended up doing the job. I lost a lot of respect for myself; I lost a lot of respect for the other people at that table. That happened 15-20 years ago—I still remember the way that fight-or-flight response hits you. I still remember that feeling.

Another time I was at a conference, a teaching workshop for new engineering faculty. And there was a breakout for an hour or two where each was supposed to teach a lesson we've prepared, and then there was peer feedback. And all these professors get up and give their little thing, and we give feedback. Then I stood up. And there was silence for minute. And then one man raised his hand—again, I was the only woman in the room—and the man said, “You should always wear red when you teach. That blouse kept my attention.” That was the only feedback I got.

Not only was I not being taken seriously, but I was feeling threatened because, What was he staring at the whole time I was doing this?

We put those in the category of the micro-aggressions. But it made me question how much I was swallowing.

Craig: In your research, as you engaged Gen Z or late millennial professionals, did you notice that they experienced harassment in a generationally specific way?

Jennifer: I would say for the most part, no, there aren’t differences. Except that Gen Z and millennials know more. They know to name it. They recognize it. And they're more likely to say, It's not OK.

I tried to watch some of my teenage movie classics with my kids, in particular The Breakfast Club, which had been a favorite of mine. I could not get through the movie, and my daughter was appalled. The sexual harassment was blatant, and it was supposed to be funny. It was the comic content. And I thought, if it's shifted that much in 30-40 years, our whole cultural context has shifted.

A very recent report said that those 18 to 29 were twice as likely as older women to report having been sexually harassed. Are women more often the target when they're young or more likely to name it? But there's some speculation, too, that older women have more support networks, emotional coping skills, maturity, all those things.

Craig: Wouldn’t the economic precariousness of a 24-year-old woman employee make them more vulnerable to harassment?

Jennifer: I think so. The research is a little bit hard to put together, but my intuition from what I've captured is that you're more likely to be harassed and you're more likely to not have power to do something about it.

I think there's this myth that, Well, I'll just go find an older woman in my company who's got some power, who's got some experience. I'm going to tell her my story. And she's gonna get me through this.

And there were plenty of stories of those older women, basically, would say, “Just get over it. That’s the way it is.” And the other response seems to be, “I can't be your champion because then I am categorized with the women, as opposed to one of the club. And so, I lose my power and credibility if I help you.”

Some men can be advocates, too, obviously, and I've known some more senior men who have been good advocates. But when you're 22 and 24, how do you know who's safe to go to if it's not your direct supervisor?

Craig: The other day I was thinking, sexual harassment is a hole in my research. So, let’s say I want to correct this—do you think I should go mostly towards the women interviewees?

Jennifer: So, there's a couple things that are true about men. To count as harassment, the person has to say it was unwanted or unwelcome. Men are more likely to take sexual interest as welcome than women are, and I think that's for all kinds of reasons that we could speculate on. But gender harassment—men don't take that as favorable.

A lot of men are sexually harassed. If you look at men-versus-women being harassed, almost all these women are harassed more than men. But those numbers of harassed men are not insignificant. If you're in a male-dominated workplace, women are more likely to be harassed. But those men who display less masculine traits are still vulnerable to it. So that seems to be gender harassment / gender policing. If men are at the lower levels in a female-dominated space, they are more likely to be harassed, and so there's some speculation that's again a gender policing—that men are supposed to be in charge. And if they're in charge, they don't get harassed.

Craig: So, women and men can both be harassed. The consequences, the emotional consequences, are very similar, even if their responses might be different.

My last question is to ask for advice for the people who read The Mode/Switch. Because I'm a communication scholar, I think about questions like, Is there a way that early-careerists can advocate for themselves? Is there a way that they should dialogue with a harasser or with bystanders?

Jennifer: This is the hardest question. When it's you, and you’re young, I don't think there's a magic bullet. You have to read your environment and figure out who's going to be your ally. In some companies reporting to HR is the worst thing you can do, so you have to have some understanding of what comes of a report to HR.

Craig: Is HR a bad place to go because they're trying to keep the company out of lawsuits?

Jennifer: That's often the case. But at some level, the company's interest should be to not have harassment, because we know that harassment kills productivity.

In some companies, reporting to your supervisor is often the best place to start. But what if your supervisor is the problem? Or what if the problem is the supervisor’s favorite person?

You're doubly hamstring. You don't know the context of your company yet, and you don't have the experience to figure out where are the safe places.

I do think the younger generation are more likely to say, “I experienced this once. I'm running down to HR. I'm making a formal report. That's totally unacceptable.”

Craig: So, fearless speech might be the only route you have in in the moment. I remember this scene in a movie that my daughter shared with me—we’re fixating on daughters and movies, apparently—it was a Noah Baumbach film, Francis Ha. There's a scene where a man touches a woman in a way she doesn’t want, and her response is to make a buzzer sound. He whips his hand back—it worked! I've sometimes thought that might be an early-career professional’s only available move: you gotta make a buzzer go off somewhere.

Jennifer: The challenge is, “She's so sensitive, so prickly. I didn't mean anything. I was just joking.”

You have to call it, but not everybody has that personality. It's very common to freeze. Did that just really happen to me? It's an hour later in the restroom when you start shaking, or it's that night when you're lying in bed. But in the moment, it's not, “You're harassing me!”

There's pretty good documentation about bystander tools. I'm wondering if you’ve been through bystander training yourself, if you could make use of that. You’re not the bystander, you're the target, but you could use it to seek out support from bystanders.

Craig: I realized after hearing your response that my question individualizes a collective problem. The wisdom of your book is to say, this should not be left up to the individual. We need to address this organizationally and structurally. So, thanks for that. Thanks very much, Jennifer, for the work you and your co-author have done. My warmest congratulations.

Jennifer: Thank you.

WILF

(or, Who I’m Learning From)

The image on top comes from the NYT’s podcast The Daily, offering an account of what sexual harassment feels like on the part of disempowered women who somehow found the courage to speak plainly against alleged abuses by Deshaun Watson.

The image on the bottom left is from a website of our current poet laureate, whose poem “Intimacy” I was fortunate enough to read in the company of some friends last Friday night at something called Qarrtsiluni, which is an Innuit word for waiting in the dark for something to happen. The poem, “Intimacy,” though, stays with you even into the light of the next day, especially for its line about how hard it is “to trust a thing that could / destroy you so quickly….”

Finally, the third image is from a Caitlin Flanagan piece in The Atlantic called “The Problem with HR,” which touches on themes Professor VanAntwerp brought up in our conversation above.

Thanks for reading the M/S this week. If you have a story in you about early-career harassment or bystander techniques you’ve found useful, I’d be grateful if you’d reach out for an interview. And, of course, I’d love to see you subscribe below! - craig