This is going to sound a little manipulative. Hang with me. Your everyday task list has one unspoken labor under everything else: persuading others to do things. Look, you need to convince coworkers to do things so that you can do things, too. If you and your team are designing a video game, say, and you’re working in a huge company with lots of other teams working on other parts of the same game, things can get choked if even just one person slows down and refuses to get stuff done. How do you convince that coworker to finish their step so you can finish yours?

Actually, my research and reflection suggest that advocative work in an organization aims in four different directions:

Persuasion upward: Think of those times when you need to advocate for an idea to people above you: your manager, your director, you veep, your CEO. The challenge of this sort of persuasion is that the person with all the power tends to think they also have all the good ideas.

Persuasion outward: Here, I’m referring to situations when you need to advocate for something to audiences beyond your organizational community. You’re trying to make a sale or forge a partnership or seek venture capital. This sort of advocacy is hard, because people outside your organization tend to have different values and vocabularies than you.

Persuasion downward: Let’s say you’re a manager of a small team. Corporate has just issued a directive to complete some HR training modules about data privacy. Your team is already busier than they should be; now they have four 90-minute workshops to complete—and you have some advocative work to do.

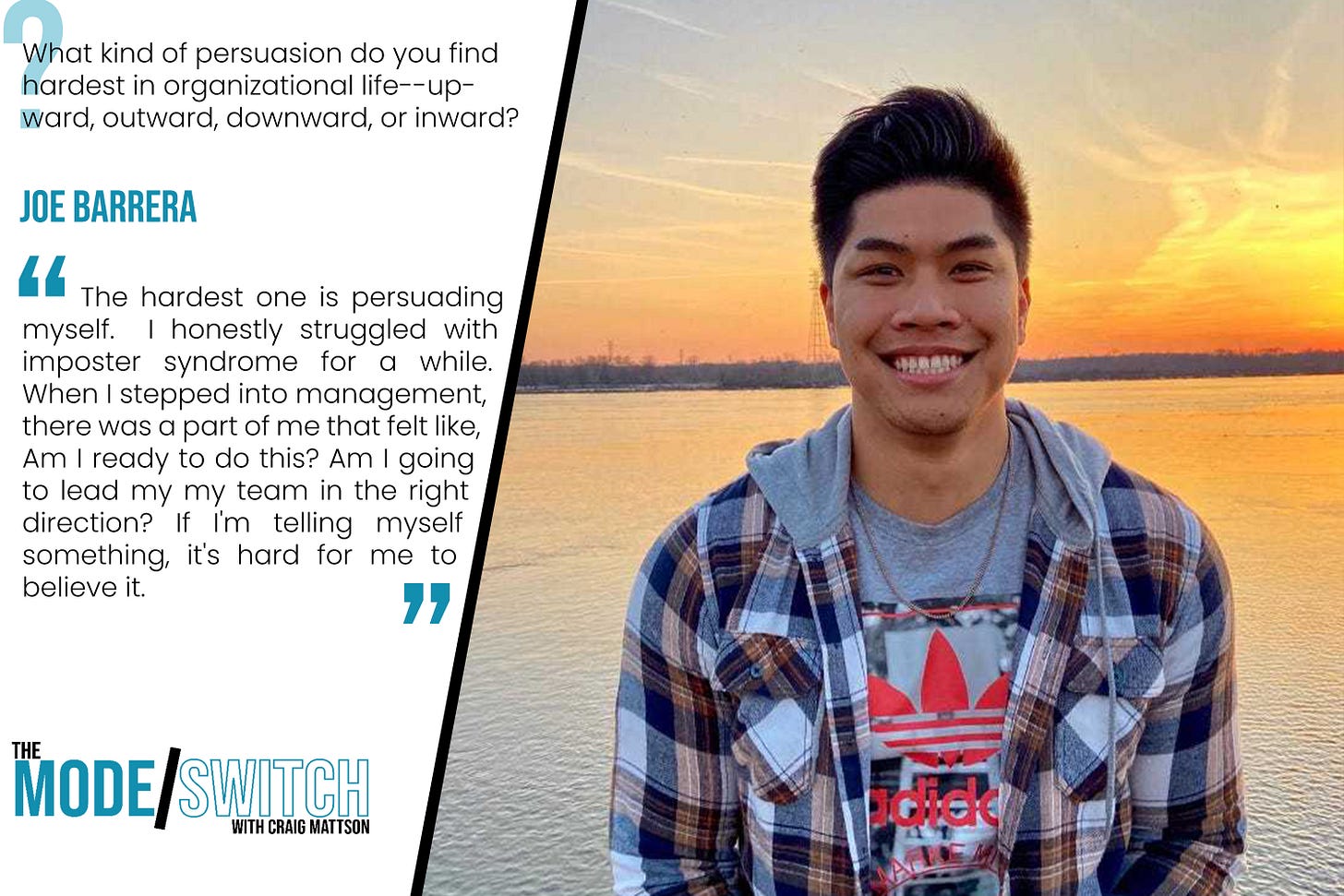

Persuasion inward: For many of us, this is the hardest of the four advocacies. Keeping a rigid mindset about things is easy. All you have to do is obey what psychologist Steven Hayes calls your “Dictator Within.” Just fuse yourself to whatever thoughts and feelings your brain generates and behave accordingly. But changing your own mind is basic to persuasion in every other direction.

Before you can persuade your manager, your client, or your team, you have to persuade yourself to speak up. You have to persuade yourself that what you’ve experienced and what you’ve come to understand are worth bring forward to others. That doesn’t mean convincing yourself that you’re absolutely right. Quite the opposite. But it does mean persuading yourself to enter into the messy work of listening and advocating.

Here’s this week’s mode switch: be willing to change your mind about the value of what you have to say. All too often, we’re welded to a negative or anxious view of our ideas. And that welding or, better, fusing keeps us from speaking up in meetings or in one-on-one exchanges. Psychologist Steven Hayes says in his book The Liberated Mind that “Cognitive fusion means buying into what your thoughts tell you…and letting what they say overdetermine what you do” (19). Your feelings of inadequacy, your suspicions of incapability, your self-skepticism, your imposter syndrome—all of it is your mind’s attempt at making sense of you. Sometimes, those thoughts and feelings are right. Surprisingly often, they’re unreliable.

Let’s say you’re working with a client who wants you to build a website for them. They want a ton of high-quality photos and lots of video animations. But you know from your extensive experience that they’re forgetting all about customer usability. They’re forgetting that a good website needs to be not just good to look at; it also needs to be easy to navigate. What do you do?

Do you go along with the customer’s wishes and start building out the site with lots of images and videos as requested?

Do you include some images and videos, but—without telling the client—make sure to arrange the site for greater accessibility and navigability?

Do you advocate for balancing aesthetics and accessibility in order to help the customer reach their goals?

This week’s mode switch means going with option 3. But that choice is hard, not just because you have to convince a stubborn client to reconsider. It’s also hard because you have to convince your stubborn self to speak up.

Your feelings of inadequacy, your suspicions of incapability, your self-skepticism, your imposter syndrome—all of it is your mind’s attempt at making sense of you and your life. Sometimes, those thoughts and feelings are right. Surprisingly often, they’re unreliable.

How do you make that mode switch?

Years ago, the philosopher Paul Ricoeur suggested that it’s wise to treat the “oneself as another.” In other words, don’t be totally fused to your self. Treat yourself as someone you encounter and then engage that self with compassion and appropriate challenge. When you make friends with someone, you don’t take everything they say without question: you provide good-natured support and resistance. That’s what I’m suggesting here, too: befriend yourself. That is, create enough distance from your thoughts and feelings that you can gradually help yourself to be flexible. Ultimately, you want to cajole yourself into saying, “Hey, maybe my ideas are worth advocating.”

Of course, there are factors that make this self-persuasion difficult.

Human history, for starters. If you entered the job force in the mid-to-late 2000s, you started your job in a time of economic jankiness. Everything felt shaky, and you felt quietly desperate. In such settings, it feels weirdly safe to fuse yourself to your own anxieties and to be super accommodating to everyone you work with.

Personal identity. If you embody a queer identity or if you’re a person with disabilities, you may face competition from others (perhaps even from non-normative folk) who see your original thinking as somehow endangering their status. Again, it feels safe just to keep your head down.

Distrust of persuasion itself. Sometimes people are skeptical of the work of persuasion, because they are worried about manipulating others, much less themselves. But to seek to change other people’s minds through reasonable argument is not essentially manipulative. It’s how human life and community take shape! And the work of persuading yourself is no less respectful of your constant need to grow and adapt to your settings.

This week’s mode switch requires inner adaptability. It entails a yogic self that can dip and stretch and bend and reach in new directions. You know what that’s going to take besides flexibility? Fortitude. In order to engage your workplace community persuasively, you need to engage yourself courageously. Go bravely!

-craig