Why Do You Talk to You?

What self-talk says about being a person. What it means for working community.

Just today I came across a Reddit thread about a “phantom whisperer” haunting workplace bathrooms. “No one knows who it is for sure,” the person wrote, “but every now and then someone will enter the cubicle next to yours and frantically whisper incomprehensibly.”

(I don’t know who needs to know this, but what Americans call a stall, Brits sometimes call a cubicle. Handy to keep in mind next time you’re in London. You’re welcome.)

If someone’s whispering in the stall next to you, they’re maybe not ok. Hard to tell. But what is going on when we talk to ourselves?

I’m not going to recommend that anyone whisper in the Porcelain Throne Room—but I will suggest that when you do, there’s something to learn.

Why Experts Recommend Self Talk

You can skip this section. You’ve already read a lot of blog posts, some written by AI, on the benefits of self-talk. Go ahead and skim forward.

Wait, what are you still doing here?

Maybe you’re interested, as I am, in the intersection of tech and self talk, I will say this (an insight I have to attribute to my daughter): the advent of the AirPod gives us permission to talk to ourselves. If someone sees you driving down the road talking away, they assume you’re blue-toothing your bestie—or recording a voicey on your phone, a practice that some 40% of Americans say has become a new mode of texting.

Only a quarter of adults report that they talk to themselves aloud. That number seems low. Are people embarrassed by the habit, sort of the way you are if you blurt something in a bathroom stall?

You shouldn’t be embarrassed—not if the social psychologists are right that muttering to yourself helps with…

focusing and

productivity and

keeping you off TikTok in unsanitary conditions.

Okay, I made that last one up. The point is: people question your okayness if you jabber to yourself in the, um, Think Tank. But even so, the socio-psych types say the habit’s good for your mental health, not to mention your multiple modes of thinking.

What’s Going on When We Talk to Ourselves?

One book I can’t get out of my head, even though I read it twenty years ago, is Wayne Booth’s memoir, My Many Selves, which tells his life story by staging a dialogue of the voices he can’t get out of his head.

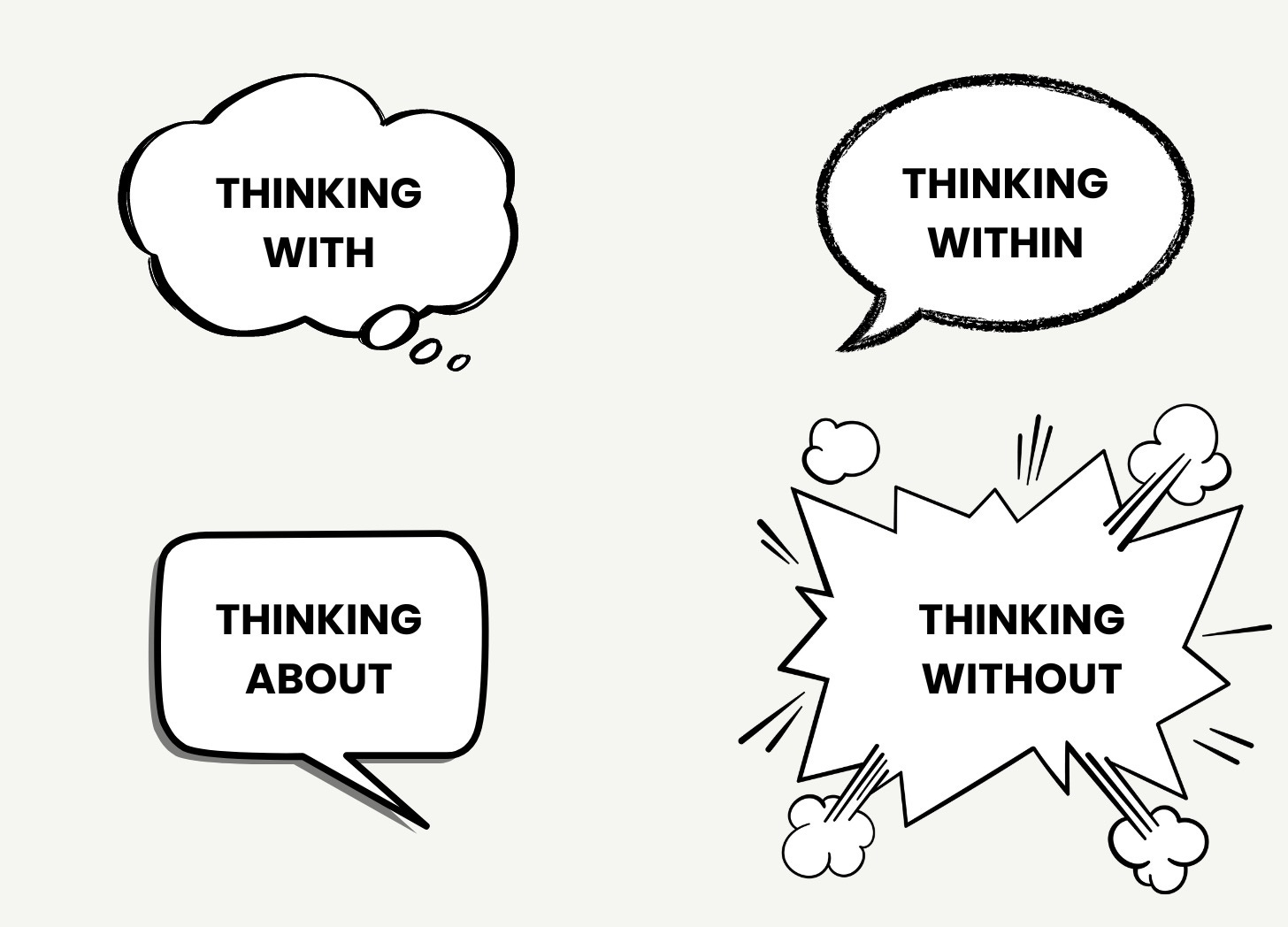

Theorists like Margaret Archer call that inner conversation reflexivity. She identifies four ways we conduct this internal exchange. Her terms are hard to access, so let’s gloss her ideas this way. If you’re talking to yourself, you might be…

Thinking With: This is what I do most often. If I’m struggling with an ethical question, I wonder, “Now, what would she say about this?” Or “What would they say right now?” That question brings someone else’s voice into the little backyard shed of my brain. Archer calls this communicative reflexivity.

Thinking Within: This is what my best friend does. She’s a lot more strong-minded than I and wants the freedom to exercise her own judgment on tough questions. Her inner processing involves fewer voices and more meditation. Such practitioners of what Archer calls “autonomous reflexivity” tend to be goal-oriented.

Thinking About: Other people, especially critically minded people, make sense of things by thinking about thinking itself. They critique frameworks, metaphors, approaches, patterns. Even if you’re not prone to this mode of critique, you probably still say things like, “I know I’m catastrophizing” or “Maybe I’m just being judgy right now, but…” Archer calls this “meta-reflexivity.”

Thinking Without: Remember the last time you had weird health symptoms, like a tingle in your left shoulder, and you looked up the symptoms online? Remember how you clicked through way too many posts? Some forecasted death within a week, and some prescribed more lima beans. In bewildering situations like that, people often experience what Archer calls “fragmented reflexivity,” or an internal conversation breakdown. Too many voices, too little coherence.

What Self Talk Tells Us

Our habits of self-talk reminds us of the reflexive creatures we are and the relational world we wish for. We’ve already talked about our innate reflexivity. Let’s talk about our world at work.

Walter Ong has argued that modern life makes things more manageable by making them more visual. You do this a lot in your job. You graph things, measure things, and symbolize things, and that visualization promises more control. Or so we fondly hope.

That control comes at a cost. By depicting reality, we depersonalize it. We set it at a remove from ourselves, looking at, rather than living with. We pixellate to predict.

So, maybe we talk to ourselves to pull things back into the world of sound. Maybe we’re fumbling and mumbling our way towards a more deeply relational world.

Sometimes, talking to yourself helps you groove with the goodness of the world. I thought of this during my workout this morning: sometimes I talk to myself, not because I am baffled or distracted, but simply because I’m happy. The joy burbles out, and the piffle bears witness that, as the poet Jane Zwart writes, “This world is made for joy.”

Sometimes, though, self-talk means your relational world has gone janky. You’re being explained rather than listened to. You’re being constrained rather than released. You’re being surveilled rather than seen. And you find yourself asking, Why so much fear? Why so much nastiness? Why so much distrust?

Why, as Dave Matthews used to say, do “these crimes between us grow deeper”?

I wonder if self-talk is a kind of “reset.” I came across the concept through The Togetherness Practice, an organization that helps changemaker communities feel less cornered, less mired. One practice they recommend is a 90-second break to reset yourself. That reset could entail breathing and silence—or maybe chatting with your soul a little.

“The practice of pausing is as old as time. And for good reason! When we slow ourselves down enough to notice our emotional and physical reactions and choose how we respond, we open ourselves up to more capacity within and around us.”

- Togetherness Practice

What’s a Mode/Switch Worth Making?

One of the first books I chose to read in grad school was Internal Rhetorics, a short book discussing how we practice persuasion on ourselves.

Here’s something I hope you’ll persuade yourself:

Self-talk isn’t problematic, but the habit might point to problematic conditions in your workplace. Perhaps your avid conversations with yourself suggest that something in your collaboration with others has become too routine. What you need is the room provided by reflexivity.

(I learned to pair those terms, btw, from Archer in Finding Our Way through the World.)

If you’re like me, when things get tough, you retreat to routine. Just do what you gotta do, right? Most managers are all too relieved if we master the procedures, perfect the process, do the dependable thing. But there is an alternative to routinizing your soul.

Allow yourself the mode/switch of returning to reflexivity. Talking to yourself’s not necessarily an avoidance. It’s not a way out of conflict or confusion. It might, in fact, be a way in to fresh forms of thought and creative ways of working with others.

I’m indebted to my colleague Fernando Santos who introduced me to Archer and gave me a good gloss on her four kinds of reflexivity. And I’m also indebted to Hannah Sherbrooke who designed this playlist, which made a good score for writing this week’s newsletter.