Issue 1, Volume 23

There’s this guy I know who used to go for long-distance runs barefoot. I should also add that the guy wasn’t telling me this out of hubris, but humility. Now, some years later, with achy joints, he has learned the lesson of listening to his body.

Not that what your body has to say is always perfectly clear, as I found out on a run one perfect October day during the Chicago Half Marathon.

I was running the Half with some friends—this must have been ten years ago—and our pace was strong and our stride-for-stride storytelling and chatter were even stronger. But then, the six-mile marker came and went—and so did all my strength. It was the strangest thing, this blunt declaration from my body, and I could hardly believe what I was hearing. I had trained all summer for this race. But still, I was, draining energy with every footfall. I threw a sidelong look at a running partner. “Not feeling 100%,” I said. “Gotta fall back.”

Two minutes later, I blacked out. A race organizer would later say he watched the whole thing on camera, as my swoopy stride turned into a nosedive. My chest hit the ground, and I didn’t come to consciousness till I’d been carted off to a med tent. I remember holding a medic’s hand. When your blood pressure’s that low, you feel like there’s not much between you and the grave.

Of course, once they’d gotten me to the University of Chicago hospital and put six bottles of intravenous fluids into me, I was fine. But why had I collapsed? The healthcare techs ran tests on my blood. They checked my heart. They looked at my lungs. And they found precisely nothing wrong. The only really and truly wrong thing was that I had to pay $1000 for a 4-minute ambulance ride.

I thought of this story of inexplicable collapse after finishing Jonathan Malesic’s recent book The End of Burnout. He opens with his own narrative of collapse, not as a runner, but as a tenured professor, doing the work he’d always wanted to do: teaching theology to undergraduate students. “By any objective standard,” he writes, “I had a fantastic job.” But just a few years before the pandemic, everything fell apart. The symptoms were utterly mysterious. “My first class was at two in the afternoon; I’d make it there barely on time and barely prepared, then go right back home when it was over. At night, I ate ice cream and drank malty, high-alcohol beer—often together. I gained thirty pounds.”

He felt baffled. “Why did I hate such a good job?” He tells about one class when an administrator came to evaluate how things were going. Malesic opened his carefully prepared discussion with a music video that he felt sure would launch the sort of collegiate conversation he’d spent all his life preparing for. But on this particular day, the students stared at him, nightmarishly uncommunicative. He felt his mouth lock and his blood rush. Keeping his voice coldly controlled, he berated the students for their disengagement—and felt humiliated by his own patronizing tone. After the students had shuffled out, the administrator, on her way out the door, suggested that maybe things weren’t as bad as they felt in the moment.

But Malesic’s vocational collapse was complete. He quit his job.

Every issue of The Mode/Switch investigates the phenomenon of early vocational overwhelm. So, of course, after reading Malesic’s moving account of early-career burnout, I had to go back to my notes and ask how the young professionals I’ve interviewed do more than get by when work’s a lot.

The name that surfaced for me was the barefoot runner I referenced earlier. His name’s Caleb Hughes, a clergyman who, at age 28, is a year-plus into his first pastoral position. In the interests of full disclosure, I should say that Caleb is not only a pastor; he’s my pastor. I first met him in person in my garage on a cold January night in 2021. We were eating Hog Wild barbecue with the garage door wide open, because the Rona was on the rampage.

As we made conversation around bites of pulled pork, I tried to take his measure. Malesic notes that “across industries, burnout is more prevalent among early-career workers.” Caleb was quite nearly the paradigm of the early-careerist, taking on a job that was burning out far more seasoned clergy than he. Today, clergy exhaustion is still common in the wake of vax and mask controversies, persistent racism, and political polarization, all of which strain congregations across the country.

But in our interview, I found that there’s a lot more to Caleb than the pulpit reveals week by week. Not just that he likes Tarantino films. Nor that he likes driving clunker cars. Nor even that he has an outsized affection for big dogs. No, the thing that caught my attention in his storytelling was how clearly he saw his own potential for burnout.

Malesic describes the three dimensions of burnout: exhaustion, cynicism, and ineffectiveness. Caleb’s life and work offer cues for how early-career professionals might stave off each of those dimensions respectively.

Say no a lot. Few things are harder for young professionals than saying no to things that might prove their worth in a precarious economy. But Caleb has cultivated what he describes as “an idiosyncratic view of time and pastoring”—by which he means, “Pastors are just really busy, and I’m not.” His clergy friends overextend themselves by saying yes to 70-hour work weeks. Caleb smiles and shakes his head to nonessential work.

Say less a lot. Like every other space in American life, workplaces can easily become politicized, making hot takes or cold cynicism seem a part of the job. Caleb’s Twitter feed confesses his identity as a “recovering cynic,” though he’s getting better at translating West Coast irony for earnest Midwesterners. But a greater challenge has been practicing kindness with people stuck at the poles of the public health debates. Caleb often maintains a judicious quiet, exchanging his native cynicism for generosity.

Say what you got. Malesic might as well have been talking to young clergy when he identified ineffectiveness as an underexamined dimension of burnout. Most people hear, “Burnout” and think, “Tiredness.” Malesic says we should think more about frustration over one’s inability to do the job. What’s lonelier than sermon prep on a Saturday night? Well, that’s easy. Sermon delivery on a Sunday morning. But Caleb deals with communication overwhelm by thorough preparation, especially in sustained practices of slow reading and deep work. And when the sermon’s feeling underwhelming, he’s candid with his congregants about what he’s found to share.

Here’s one problem with this week’s Mode/Switch so far: it could be read as putting all the responsibility for your burnout on you. In fact, Malesic’s book joins an already expansive conversation among people writing about the structural causes of personal exhaustion. Many of these voices—like Anne Helen Peterson and Tiana Clark—rightly point out that you can’t stave off burnout on your own. It’s a cultural problem that has to be addressed collectively.

But still, Caleb’s story suggests there are choices you can make to keep burnout at bay. And sometimes when it feels like there’s not much between your soul and the ground, it really helps to push away from your work and go out on a run. Just don’t go barefoot.

Who I’m Learning From

You might dismiss these parking lot attendants as over-educated and under-employed. But give this movie a watch. You’ll see that judgment needs revising. What they have to say about the character of work in America is worth rewatching again and again.

Jonathan Malesic’s The End of Burnout

Malesic’s story resonates of vocational collapse and resurrection will resonate with people across the professions. But it hit me especially hard, because I am myself a tenured professor who’s just resigned his position at Trinity Christian College to take up an endowed chair at Calvin University. Dear Dr. Malesic (I want to say), your writing’s a little too on the nose.

“How Millennials Became The Burnout Generation” by Anne Helen Peterson

If you’ve ever suffered “errand fatigue,” by which Peterson means the inexplicable inability to do the simplest, most ordinary things in everyday life and work, you are almost certainly burned out. But Peterson helps you know why you’re not alone.

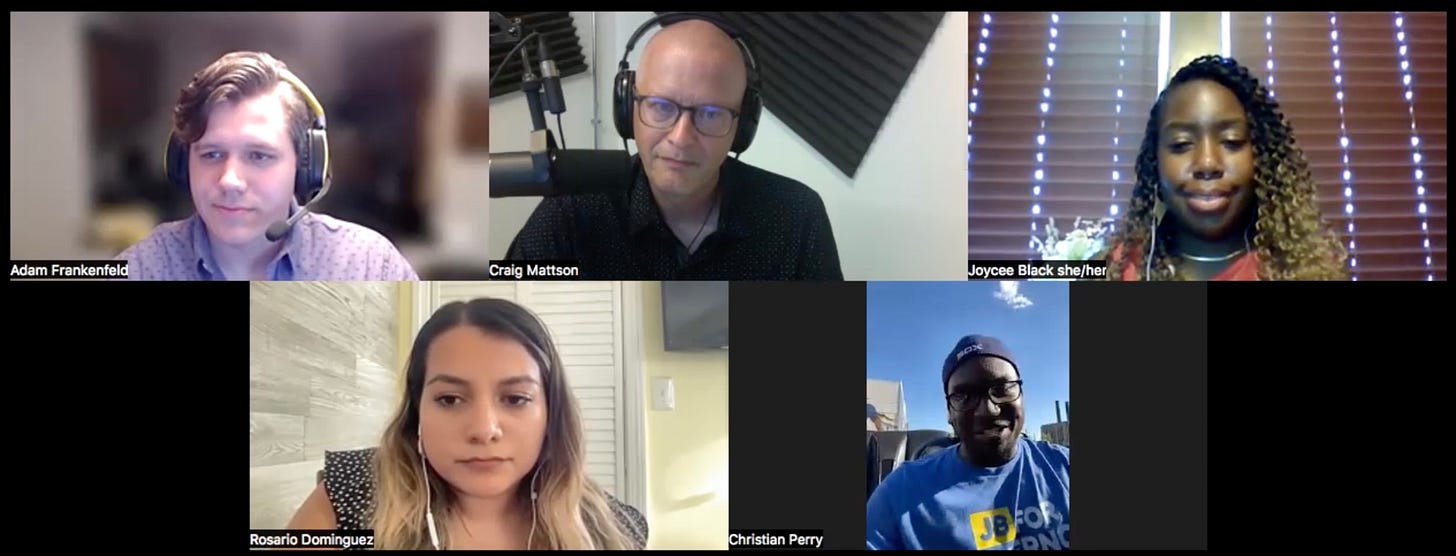

On Wednesday afternoon this week, I had the chance to capture on video a conversation with four early-career professionals—the first-ever Mode/Switch Videochat. Tune in next week to see that exchange! - Craig